NOTE: Within seconds of publishing this review, I realised that a new and major update had been released the day before, introducing many of the features people had complained were missing from the game and making significant tweaks that will radically affect game-play. No doubt, by the time I get around to reviewing these changes, it’ll change again, but it is certainly pleasing to see that the changes have been made and it vindicates my faith in Hello Games and their continued commitment to making this great game even better. The Foundation Update notes can be found here.

No Man’s Sky ended up having a pretty rough landing. Within the space of a week it went from being the most anticipated game in years, to making some of the most successful sales figures on release, to being flamed by users and put in its place by lukewarm reviews. Many players felt greatly disappointed, if not cheated and there has been a flurry of buyers asking for their money back. More recently the developers, Hello Games, were subject to a false advertising probe after claims that the content showcased in the trailer had not materialised in game and that the promotional material was therefore deliberately misleading. Company director and key designer of the game, Sean Murray, has seemingly gone to ground, with some speculating that his lack of communication suggests the independent studio has in fact been abandoned and that there is no intention of fulfilling the promises of further updates and expanded content, though this is unsubstantiated rumour and speculation.

What lies ahead for No Man’s Sky?

Much of this criticism feels unfair towards a game that, in spite of what it lacks, still offers a great many magical experiences and is an important milestone in procedurally generated game-worlds. It is also pretty rough on the developers, who are a small, niche company without the massive resources that usually underlie such ambitious game developments. Perhaps Sean Murray needs to learn a thing or two about public relations, but, considering the manner in which haters, trolls and flamers on the net make their feelings known, he can hardly be blamed for stepping back while this shitstorm of nastiness runs its course.

Looks like a shitstorm ahead…

Personally, I think Sean Murray and his colleagues at Hello Games should stand up and take a bow, for No Man’s Sky is a magnificent piece of work. For three weeks I wanted to do nothing more than explore this effectively endless galaxy and had no trouble in clocking up almost a hundred hours before running out of steam. Unfortunately, despite this seeming a worthwhile return from any entertainment product for a mere 50 odd dollars, (consider what you pay for a film at the cinema and how long it lasts) many people assume that the game should go on providing hundreds, if not thousands of hours of gameplay. Arguably such expectations are built into the game’s very premise. A galaxy that is, to all intents and purposes, never-ending, certainly suggests limitless play, but then again, arguably, the game delivers precisely that. Despite there being significant limits to what one can do in the game, there is absolutely nothing stopping players from continuing to explore this universe for decades.

So, where do you draw the line? There are many games which cost the same price and which can be completed in under ten hours. Do people ask for their money back with those titles? It all comes down to expectations, many of which were inflated not merely by Hello Games’ promotional material, but by players’ overzealous imaginings of what might indeed be possible.

Not good enough?

Having said that, there are many legitimate criticisms of No Man’s Sky’s core promise of seemingly infinite procedurally-generated variety. Reviewers and gamers have complained about the shallow pool of elements which go into generating the planets, their lack of flowing water and the universal climates which prevail, with no distinction between the equatorial zone and the polar regions. Others have complained about the simplicity of space-battles and the absence of the more grandiose encounters hinted at in the promos, along with the general lack of game-play. It is not possible to craft anything beyond upgrades for one’s ship, Exosuit and Multitool, and once these have been taken to a decent enough level, there is little incentive to find resources, except for fuel, survival and trading, which are really just ends in themselves.

Maxed your equipment? Just relax and enjoy the scenery

No Man’s Sky is, essentially, a survival and trading game, and on both counts, it has its limitations. You will spend much of your time monitoring life-support levels, recharging your shields and equipment and firing your mining laser at crystals, vegetation and ore deposits.

This sets up an at times tedious loop of resource extraction, finding a place to sell the goods, cleaning out your inventory, and then rinsing and repeating the whole thing over again. Survival in No Man’s Sky is also relatively easy, though this depends on the environment and climate. There’s rarely a shortage of elements to mine to recharge one’s suit and the biggest challenges usually come from the climate and weather. The good news is that it’s really up to the player to choose what level of challenge they are willing to accept. No Man’s Sky can be played slowly and safely on a clement world with mild temperatures and a hospitable atmosphere, where you can walk at your leisure and hardly ever have to charge your suit, or it can be played intensely in hostile environments where you are forced to seek shelter continually from radiation storms and icy blasts that send the thermostat below a hundred minus or up to 400 degrees centigrade.

Frozen goggles

328.5 Celsius – ouch

The challenge is also increased depending on the local attitude of the Sentinels. These are basically automated flying cameras with guns, which can be violently hostile on sight, or completely ignore your presence. Upon first landing on a planet, the relative degree of hostility is revealed by a rating, such as “passive”, “hostile” or “frenzied”.

Sometimes even looking seems to set them off…

So much for paradise if you get attacked on sight

Much of the time they will ignore you, but mining too much of a material or destroying too much plant or animal life can really tick them off. There are also particular rare items that can be looted on planets such as Vortex Cubes or Albumen Pearls, and these will set the sentinels off irrespective of their attitude rating. “Frenzied” sentinels are, as the name suggests, cranky mofos and they will attack within five seconds of sighting the player. Either way, the sentinels are disappointingly easy to deal with and are more of an annoyance than anything else. They can also spoil immersion at times with their whirring gears and pulsing power sources intruding into the beautiful atmospherics.

Don’t scan me, bro

Careful what you harvest, it may anger the Sentinels

The ease or difficulty of play will inevitably appeal to different temperaments or moods. If you are happy just to wander in a pleasant, immersive environment and enjoy its beauty or bleakness, then the game offers such opportunities in spades. If you long for intensity and danger, it’s pretty easy to find a planet with an extreme environment to up the stakes.

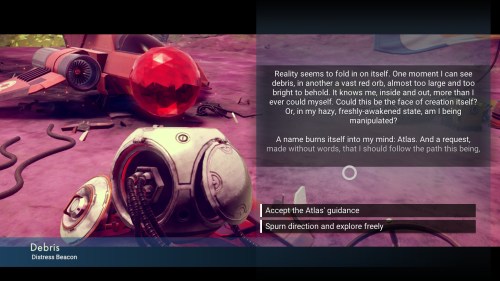

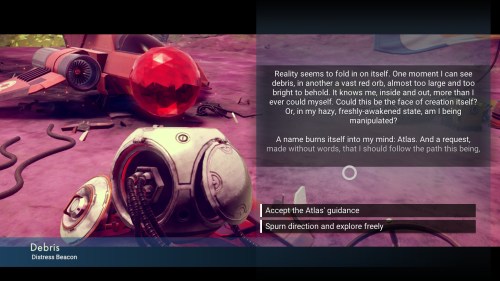

The game begins on a random world, and consequently all players will have a very different starting experience, depending on the climate, environment, etc. The first job is to repair your ship, which offers a brief and not entirely intuitive tutorial-like opening, before moving onto the task of building a hyperdrive to allow you to travel between the stars.

An early choice in the game, though the decision is by no means irrevocable

Struggled to find Zinc at first. It’s in the yellow flowers…

Each planet, however, is, well, planet-sized and initially offers a huge range of exploration options. It is entirely possible to remain on the one planet forever and continue exploring, crafting and improving one’s equipment as, it seems, one player famously did in the days immediately after release.

These pods can be used to purchase Exosuit inventory space

All planets contain a number of alien outposts, scattered about in densities that vary from world to world. These outposts come in a number of different forms; some being small research stations with a couple of shipping-container sized habitations, while others are more complete complexes – observatories, command centres, trading posts and spaceports.

Space station stock exchange

These trading interfaces can even be found floating at locations on the surface of a planet

These can be found simply by flying over terrain and looking for signs of structures, using the scanner on one’s ship, or, with the help of an easy-to-craft bypass chip, using the Signal Scanners which are often found at these outposts.

Some of the larger outposts are occupied by one of the three different alien races in the game: the Gek, Korvax and Vy’keen (shown below, respectively) none of whom are hostile, though they can get pissed off at times.

The encounters with the aliens are initially intriguing, if somewhat sparse and minimalist in dialogue, yet, limited though it might be, the dialogue is a puzzle in itself. One of the great innovations of No Man’s Sky is the ability to learn three different languages, which gradually improves your capacity to communicate. To begin with, they speak mere gobbledegook, but as you flesh out your vocabulary with key words, learned from Knowledge Stones, databanks, ancient alien sites, electronic encyclopaedias and encounters with other aliens, it becomes possible to make out enough of what they are saying to choose the appropriate response.

The learned words, should they be used, will appear in English in the dialogue transcript, giving you the chance to decipher the overall meaning. This process is aided by one’s intuition, for the player is offered text-based insights into the actions and possible desires or intentions of the alien interlocutor based on observation of things such as body language or mood. This can at times make it very easy to choose the right response, but certainly not always.

Say what?

The Alien ruins are attractive structures which allow the player to interact with them and usually face a choice with a chance for a reward. These often contain engaging story elements that can be quite emotive, but they also offer a chance for new equipment, upgrades, language learning and the chance to increase one’s standing with the alien races – a sort of diplomacy level that gives you more options in dialogues.

These encounters also allow the player to learn new blueprints for technology which can be crafted. Blueprints can be acquired in a number of ways – through aliens, from wrecked machinery, crashed spaceships and various interactive terminals inside alien buildings. The blueprints are essential for improving the capability of your Exosuit, Multi-tool and spaceship, though the number available is disappointingly limited. After a flurry of discovery, you will find yourself constantly being told that the blueprint you discovered is already known.

The only blueprints that seem almost impossible to find are those for the Atlas Pass 1, 2 and 3. Countless locked doors and containers in the game require one of these passes to open, and even after 100 hours of play, I’ve still only found the first pass, which opens practically nothing.

By contrast, within only around forty hours of play, I had already maxed out my tech knowledge for the suit, ship and tool, which rather made exploring seem a whole lot less worthwhile. And ultimately, this is the main problem with No Man’s Sky. There is a feeling that sets in rather too early that there is actually almost nothing to do.

Crashed ships can be claimed and repaired, though they are usually of a lesser quality than your own

There is certainly a lot of repetition in No Man’s Sky and this ultimately occurs in pretty well all aspects of the game. Outside of game-play itself, the terrain certainly has its limitations. The cave interiors on planets are universally built on the same template, with only minor variations in the undergrowth and shape of the mineral outcrops. They might be a great place to find valuable crafting materials, and initially very attractive, but they become all too familiar pretty quickly. Other frequent repetitions are the mushrooms which grow even on planets that are supposed to have no fauna, the large succulents which I call “jazz hands” and the iron ore outcrops, especially the ones that look like big upturned thimbles with shrooms sprouting from them.

Jazz Hands aplenty

Underwater life is restricted to some very similar designs in flora, fauna and mineral deposits, though this does not in any way detract from the pleasure of swimming through these landscapes.

Beautiful and smooth; underwater life in the variously coloured oceans

The range of surface temperatures also seems somewhat limited. Nowhere is really ever as cold as Pluto, nor do they get much hotter than a few hundred degrees, and then only during a fire storm.

Extreme Toxic rain and hostile creatures, best to get off this planet quickly

All these elements are thrown together in different ways on every planet, but once you’ve visited around forty or so planets and moons, most of the terrain, rock formations, flora and fauna will all start to look familiar. And yet, there is no denying that plenty of those combinations are breathtakingly beautiful or astonishingly bleak and planets can be a delight either to walk around or fly over.

How anyone could not find beauty in this game is beyond me

From space the planets seem majestic and inviting, or daunting, forbidding and mysterious. At times the nature of the surface only really becomes visible on close approach, or even during descent as the terrain resolves itself from the fog of the distant LOD. The first sighting of a world covered with oceans is thrilling, as are the green ones offering abundant life; such welcome and familiar sights.

Green oceans ahoy!

Another barren furnace?

Spoiled for choice

Breathtaking science fiction vistas abound

The star systems in the game come in different colours, Yellow, Red, Blue, Green which require different types of warp drive to access.

The more difficult to reach systems offer richer pickings with regard to exotic and rare resources, but might also offer a more hostile welcome. They tend to contain more water worlds, which seem rather prevalent around green Type E stars. I personally had some gripes with the make-up of planetary systems, which are entirely devoid of gas giants.

Many planets, but always just the one sun

Perhaps it just seemed pointless including planets whose surface could not be visited, though it would have been fun to let us learn the hard way not to fly into the crushing pressure of such beasts. Either way, the game feels less realistic as a consequence. Would it have been that difficult to throw a few into the algorithm, or even allow players to visit asteroids? There are also no binary systems, despite the fact that roughly 85% (yes, that’s correct) of known star systems in the Milky Way are binary or multiple systems. Gravity is also identical on every world and, while I can accept that it might have been no fun at all trying to move around on a planet with gravity ten times that of the Earth, surely this could be rectified with an Exosuit upgrade, and, on the flip side, it would have been a hell of a lot of fun to bounce across the surface of a low-gravity planet. I accept that this is a different galaxy and possibly a different universe, and hence it is up to the designers to choose the physics of this universe, which, are, to say the least, odd, considering the number of floating rocks and minerals to be found on planets. Still, binary worlds would have been a chance for even more beauty in the game, of which there is plenty, and which is never a bad thing.

Wonderfully bleak

There is also very limited information about the planets and the arrangement of these systems. Could we not know the distance from their star more readily? This is only really shown when heading towards a planet, and then only with regard to the time it takes to arrive there from your present position. That’s great if you want time to smoke a pipe, but not so great if you would like to know which planets are closest to the sun, something that is not always obvious. Could the ship scanner not provide a map showing their orbital paths relative to each other, as in Mass Effect? And with that in mind, what is the mass of these planets? Their diameter? None of this information is available and it’s disappointing for people such as myself who are obsessed with the dimensions of exo-planets and the many new dwarf planets we keep finding in our own system. Sure, we can see that some planets are much larger than others, but I’d like to know whether I’m on a super-Earth or a Ceres.

Some pretty super earth-like worlds

The malleability of the terrain on these worlds is impressive and offers a lot of freedom. I’ve gotten utterly lost in underground caves before, unable to find a way to the surface and ended up blasting my way through the cave roof. Your scanner becomes your best friend in such situations, as it also reveals objects that are above you, allowing you to judge roughly how much rock is over your head. If you pick the right spot, you can blow holes in the rock with plasma grenades and, when the sky becomes visible above, simply jetpack out of there and kiss your claustrophobia goodbye.

No way out? Blow a hole in the roof

Even when there is a lot of rock, you can blast a tunnel as high as your jetpack will allow you to fly, punch a ledge into the side of your shaft, and then get back to the job of blasting the rock above your head until the light breaks through. Now that’s cool. And, this strategy works both ways. Standing on top of a huge deposit, but unable to find an entrance to the cave system? Hey presto, just plasma grenade your way through the ground until you drop into the cave, or blast a tunnel as long as you need through the side of a mountain.

A tunnel I dug myself, from one cave to the next

Being underground, or even just out of the wind, ensures that any harmful environmental effects are negated and this makes blasting a hole in the rock and hiding in it a great survival strategy in extreme environments.

As if it wasn’t hot enough already – Radioactive storms!

Don’t go too far from your ship or shelter on extreme worlds. Even the best protection won’t last long

Another close call

In such hostile places, particularly when a storm strikes, the thermal protection bar will drop like a stone and you might well be caught in the open, too far from your ship to make it home. Many times I’ve had to run desperately underground, find a shaded windbreak, or blast my way into the rock, or the base of a mineral outcrop to create a sheltered cave. You can also exploit this terrain destructibility to mine safely in extreme environments.

This used to be a huge Heridium deposit. Time to put in a swimming pool…

If you begin by blasting away the base of a mineral outcrop, you can climb into the hole, stabilise your thermal protection, and fire your laser upwards to mine the wealth overhead. Fortunately, on account of the strange physics in this game, the material never collapses on your head, even when none of it is left touching the ground. It just hangs in the air, as do huge floating hunks of copper and occasional rock platforms on some worlds, reminiscent of the Hallelujah Mountains in Avatar.

Floating rocks!

As stated earlier, mining resources can become a little tedious after a while and it’s best to mix this up and not become too obsessive. Though mining is strangely compelling, it does get rather boring standing in the one spot and blasting, or “lazing” away at a gleaming chunk of aluminium, for example.

The Swiss-cheese approach to ore extraction

It is perhaps more exciting to venture into cave systems and head towards the grey treasure chest symbols revealed by the scanner, which indicate the most valuable metals. These cave networks can extend for very long distances and the further one ventures inside, the more one is rewarded with richer deposits, usually found in the green crystalline forms of Gold, Aluminium or Emeril.

This at least makes the process of ore-harvesting more dynamic. It’s just a pity all the caves look pretty much the same, though they are, in their way, attractive spaces and there is something thrilling about watching the scanner burst like a wave through the tunnels.

Predators can also significantly raise the tension, particularly when trapped in a cave with them. Most of the time hostile animals will seem a mere nuisance, doing little harm and being easy to flee from. Yet, on occasion, when they appear in numbers in an extreme environment with other stresses already upon you, they can prove to be very dangerous.

This thing was annoyingly bitey

All those red paw symbols are hostile creatures

Such was the case where, trapped in a cave, hiding from a freezing storm, I was cornered by four scorpion-like creatures who bit the hell out of me before I managed to blow a hole in the wall and climb out of their reach. Of course, you can just kill them, but they take a surprising amount of damage at times and the gun can be frustratingly crap at hitting the target at times.

Fortunately, he was friendly

All this variation in the intensity of the game-play means that it can be heart-pumpingly challenging at times, and immersively relaxing at others. Yet, after a while, when one has discovered many worlds, fleshed out all the available techs and upgraded equipment sufficiently to overcome all challenges, it begins to seem rather pointless. At present, after a hundred or so hours of play, my Exosuit and Multitool are sufficiently maxed to overcome any challenges and I struggle to see any reason to upgrade my ship, which already has the best possible warp-drive and seems able to win any encounter with hostile spaceships readily enough.

Sure, I could improve my cargo capacity, but why? It’s easy enough to haul loot back to a space-station, or find a trader on the surface of a planet, which rather makes it an end in itself. This sense of pointlessness is not aided by the fact that it is not possible simply to start the game again. I thought I must be missing some fundamental option on the menus, but Googling this shows that there is no way to start afresh, without going through a relatively complex process of editing files and directories. You could of course just abandon your ship and start again with regards to your equipment, but you would still retain all your skills. The languages, fortunately, seem far more abundant in the number of words that can be learned. This must be a significant reservoir, because even after having learned hundreds if not thousands of words, the aliens still speak nonsense at me more often than not.

There is certainly a narrative to the game and one is encouraged gradually to find one’s way to the galactic centre, where I imagine some kind of endgame kicks in, but I haven’t made it there yet and refuse to spoil the surprise by reading about it. Your journey there is made possible by visiting the Atlas Interfaces which can be found in some systems. These also offer a chance to learn a large number of words from the glowing balls which occupy the gleaming floor inside the Atlas Interface and to gain Atlas Stones, which are apparently needed when one reaches the galactic centre.

Another magnificent and slickly rendered interior

Some systems contain Space Anomalies – a kind of space station – all of which contain the same two entities: Priest Entity Nada and Specialist Polo, a Korvax and Gek respectively. These two cheery fellows can set you back on your path to the galactic centre, give you tech blueprints and other rewards based on your achievements so far. For example, having spent five or more days on extreme worlds will open up a reward for your intrepid exploration. The problem is, as always, that you will probably know the tech blueprint offered already. Polo can, however, on first encounter, give you the Atlas Pass blueprint, which literally opens a lot of doors.

The Milestones and achievements offer some minor incentive to pursue certain targets, yet most of these are merely incidental to what you do and can be racked up easily enough without actively pursuing any of them. Also, as is the case with learning new techs, these Milestones – for things such as distance walked, number of warps between planetary systems, or alien ships destroyed – seem to dry up pretty quickly. There is, all the same, something special about these moments, which are nicely done.

Yet, either way, the main idea of this game was always to explore and map at least some small part of this vast galaxy with its much vaunted 18 quintillion planets. The developers make it very clear in game that the main story is optional, and its intrusions into the game are minimal to say the least. Exploring, in itself, is great fun and there is a real joy to be found in naming planets, star systems, flora and fauna. After a while, however, this too becomes repetitive and feels a bit like a chore, somewhat akin to that old RPG bugbear – inventory management.

Much of this sounds rather negative and potentially off-putting, but I would still strongly recommend No Man’s Sky. The initial rush of discovery, the freedom and beauty, the ease and smoothness of it all is intoxicating, at least for a while. The game also looks spectacular. Yes, it’s stylised and not hyper-realism, but the colours, clean lines and aesthetic design make a gorgeous whole. It is also accompanied by a fantastic soundtrack by Sheffield band 65daysofstatic. Minimalist and unobtrusive, the music complements the loneliness and emptiness of this vast galaxy, offering eerie moods and subliminal cues that can set the tone of one’s imaginings. This is important because No Man’s Sky requires some imagination to give one’s actions and travels a sense of purpose outside of the very sparse and optional narrative elements of the game. At times you get as much from this game as you bring to it. There are 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 worlds, which, it has been estimated, would take one player 5 billion years to explore, and then only if they visited for one second, not counting travel times in between. That is, to put it bluntly, an effing big sandbox with a heck of a lot of sand. Even after a hundred hours of play, I still find great pleasure in visiting a planet for the first time, seeing its sights and knowing that no one else has ever been there before.

Another great aspect of No Man’s Sky is the smoothness with which one can transition from one environment to the next. With an easy, simple flow, it is possible to descend from space, rumbling through the atmosphere, cruise down and land beside an ocean, jump out and plunge straight into the water. The jetpack allows for easy avoidance of obstacles and dangers. It constantly replenishes itself and doesn’t need fuelling, but even with upgrades, the burst is relatively short-lived; enough to scale a height, get across a narrow canyon or break your fall on a long descent. Swimming underwater is also a pleasure, as much in its beauty as it is in the sense of relief from often harsh environments.

Fancy a dip?

Flying is a breeze; a smooth and elegant ride. You can coast in a sort of crash-proof autopilot, or lean in and speed across the surface. Space has an easy driftiness to it; punch in the engines and zoom towards a planet, float about and pick off asteroids for minerals or even blow a hole in one of the bigger ones and fly straight through it. Space battles are hard at first, but soon become rather routine; yet they remain fun – a bit of sport before you get on with the job of trying to find some meaning in all this.

Eat your heart out, Dennis

In space you will come across drifting freighters that warp right into one’s locality when you switch off the pulse engine. Occasionally they send distress signals; seeking help in dispensing with pirates. They can even be attacked if you are feeling brave or suicidal enough. Their hulking designs are attractively industrial, like the epic ships pictured in the sci fi books and games I fed on as a child, and it is a pleasure just to fly alongside them for a time.

Careful where you shoot in a dogfight, as a few stray shots can bring retaliation

Equally the range of designs of individual ships offers some real curiosities. Many of the ships look awkward, asymmetrical and un-aerodynamic, while others are sleek and streamlined. If you see one you like, in a space port, trading post or space station, it is possible to speak to the pilot and purchase their ship, if you have the vast sum usually required.

Entering the atmosphere of a planet, one is met with a roaring of wind, a reddening of the screen’s edges and a bumpy ride.

Atmospheric entry is very atmospheric

If you don’t get the angle right or slow down, you can bounce right off the atmosphere and veer back up into space, though this is easily corrected and hardly hazardous. As you near the surface, the features slowly resolve themselves into focus, often resulting in the vanishing of apparent features that were a mere mirage from the upper atmosphere.

Lovely lakes? Or is it just a mirage?

Oceans or clouds?

What one supposed were lakes might dissolve into valleys and canyons as the detail sharpens. This can be an exhilarating ride, swooping over oceans, mountains, forests, grasslands or sandy dunes. Humps of precious metals and geometrical towers of crystal poke from the surface; alien outposts can be spied, and every inch of it is open to visit.

Flying over the surface of a new world is a great pleasure

Such is the immersion offered by this game that one’s emotions are often affected by the nature of the environments. Hot and dusty places make me anxious and thirsty, the cold and windswept have me longing to turn on the heater, while in lush environments I feel relaxed and happy. The excellent environmental sounds in No Man’s Sky enhance the game’s immersiveness. Rushing winds, pouring rain, haunting echoes and the eerie cries of strange beasts lend the stylised visuals an authenticity that reminded me of The Long Dark. The calls of the wild are even more remarkable for the fact that they are modified according to the randomised throat structure of the procedurally generated creatures.

Hear the haunting bellows of the Long-finned Punchohat echo across this frozen world

An animal with a long, thin neck, will make a sound akin to such a creature on Earth, making the implausible seem, well, plausible. This is just another fine example of the many things that No Man’s Sky gets right. It really is a clever and beautiful game, slick, smooth, graceful, even sexy in its bold, futuristic colourings. It is one of the most immersive games I’ve ever played – high praise from a hardcore immersionista.

Already this game has provided me with some of my very favourite science fiction moments. On a world of blue oceans, iron-red rock and dunes, I chased three ships halfway across the surface, hoping they might lead me to a trading post. In that friendly chase we dipped and climbed over land and sea, cruising across mountains, skimming across the surface of the waters; colourful contrails streaking from the jets of this trio of attractive ships. I soon forgot about my overfull inventory and flew half-way around the planet in their wake.

Had I wanted to, I could have shot them down, but in such a lonely universe, without other players or anyone else who speaks my language, this random moment of bonding, entirely of my own generation, felt palliative.

The sense of loneliness in No Man’s Sky is one of its strengths. Never encountering another of your own kind and spending much of the game in vast, open spaces, venturing into mostly empty buildings, leaves the player with a sense of loss as well as a sense of being lost. In the small, rectangular habitats which are always unoccupied, one can switch the light on and off or swivel the chair and watch as it spins slowly to a halt; actions which become symbolic of a yearning for familiarity, for comfort and company in all the emptiness. The aliens, despite their occasional warmth, merely add to the loneliness with their preoccupied distance.

Empty chairs and a light for no one. Evidence of habitation abounds, but not a soul to be found

Yet there is much relief to be found in sheer beauty, though this too is tinged with the sadness of experiencing it all alone. On my favourite planet of all, Leura Falls, the most Earth-like yet discovered, I strolled through swathes of shifting green grass, admiring the pink trees and bright blue skies and the vast blue oceans with their sandy shores. With a comfortable temperature of around 8.2 degrees and a benign atmosphere, I could explore for very long periods of time without ever having to charge my life support. Even the frequent freezing storms, which sent the thermometer plummeting to -23, hardly bothered my thermal protection. The shifting colours from dawn to sunset were mesmerising, soothing, awe-inspiring. It was very difficult to leave, and, indeed, I went back there for a while, missing its easy-going mildness and abundant, attractive life. I would love for others to visit this place, yet what are the chances of this happening in such a vast galaxy?

The strange beasts that inhabit the worlds can also be a delight and a source of comfort. When the creatures are not hostile, it is possible to interact with them and feed them. This makes them happy, as indicated by a floating happy face above them, and they will then lead the player to a reward of some kind – usually a rare isotope or somesuch, but of pretty meagre value.

The way to his heart is through his stomach

The fauna comes in different densities and some planets can be teeming with abundant life, while others contain a few scattered creatures. The variety of the animals is inevitably limited by the range of options available to the algorithms, but while many similar creatures have appeared, some of them have been wonderfully varied, amusing, and, at times, utterly ridiculous. The numerous species of “Sloppenders” (my name) had me laughing myself silly on first contact.

Strawberry Sloppender – named after the heavy pillow that was banned from childhood pillow fights

Some players have complained of glitches, crashes, issues with frame-rates locking up and the like, but from the day of release, I’ve had no such issues at all. Indeed, I was greatly impressed on first firing the game up at how seamless it all was. I saved the game frequently to avoid any catastrophes, but soon found this to be unnecessary as the game has never crashed. NOT ONCE. As with any game, there is a learning curve, particularly with regard to crafting and understanding what is worth keeping extracting or looting. You will also likely come out of your first space battle the worse for wear, if you don’t simply get blasted out of the sky, but this is ultimately an extremely smooth game with an elegant flow and ease of movement and play.

No Man’s Sky is a Milestone in itself

No other game has yet come close to No Man’s Sky in attempting to realise the incomprehensible scale of the galaxy, let alone the universe. No other game allows the exploration of so many fully-rendered environments. Our galaxy alone contains more than two hundred billion stars and an even greater number of planets yet to be discovered. It is unlikely that we will ever be able to explore it so freely as we can in a game, but by simulating such a vast and unexplored space and the wonders it must contain, certainly in geography, almost certainly in other forms of life, it might encourage us to try. Getting through the next hundred years is challenge enough, but if we are still stuck here in that unimaginably distant future when the Earth can no longer support life, then we’ll really be in trouble.

Future Earth?

If you are content with an open world (galaxy) that allows you to explore extensively, to construct your own narratives, pursue your own goals and to revel in the moments that come at random, rather than necessarily as another complication or climax of the narrative, then you will find a lot of possibility in this game. That one cannot construct a base or space-station or anything else beyond a ship does place some limits on realising your imaginings, though I suspect this is designed to encourage players to continue exploring and not merely bunker down on a single world. Such options, however, have been promised for future updates and the game’s critics may yet be answered with new and significant content. Yet, even without any further updates, the game is still worth playing in its present form. The joy I received across tens of hours was worth every penny and I continue to get pleasure from No Man’s Sky. It might be a flawed masterpiece, but it is, in fact, a masterpiece.

You must be logged in to post a comment.