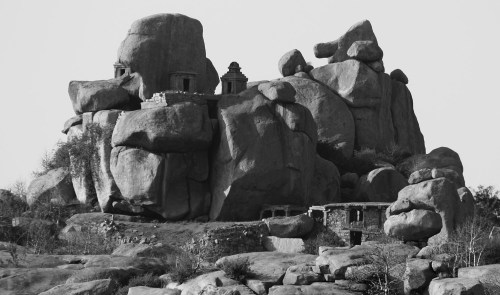

Hampi is a striking place – an odd landscape of giant, tawny granite boulders, strewn across dry river plains and low hills. The weathered, rounded rocks protrude from the rusty, orange soil like scattered marbles, giving the place an otherworldly feel. Hampi is not only a geological wonder, it is also an archaeological one. Having once been the capital of the Vijayanagaran Empire – at its height between the 14th and 16th centuries – the site is full of monumental stone ruins – covering a whopping 26 square kilometres.

The city of Vijayanagara was founded on the Tungabhadra River in 1336 by two brothers – Harihara and Bukka, and quickly rose to become a major centre of trade and Hinduism. Its wealth came primarily from cotton and spices – a market monopolised by the local rulers to great effect. With such ample stone reserves to be quarried, Vijayanagara experienced an extended construction boom which peaked in the early 16th century under the rule of Krishna Deva Raya (1509-1529). It is from this time that many of the major structures are derived; vast temple complexes and colonnades, bath-houses, cisterns, aqueducts, palaces and elephant stables.

Much of the architecture bears similarities to Hindu structures elsewhere, particularly with regard to the temples, yet Vijayanagara also reflects a local bent for ingeniously blending its buildings into the rocky landscape. It is a busy style, sporting countless high relief carvings and patterned motifs which give the buildings an organic quality.

At its height, Vijayanagara, which means, city of victory, had a population somewhere upwards of 500,000 people, making it the second largest city of its day – surpassed only by Beijing – and a rival to ancient Rome. Vijayanagara fell not long after reaching its peak – sacked by a coalition of Muslim rulers from the north – the Deccan Sultans, who defeated the Vijayanagarans at the battle of Talikota in 1565. After the 16th century, the city fell into decline and ultimately, ruin.

Vijayanagara, and modern day Hampi, are both major sites of ongoing archaeological activity and popular tourist destinations. The town itself – Hampi Bazaar – is tiny, a mere village of neatly swept dirt streets populated as much by animals as people. The town was, until very recently, a good deal larger. Concern about overdevelopment and the locals’ tendency to re-use the ruined buildings as dwellings or for commercial purposes led the local authorities to demolish a number of structures built in the last 50 odd years, and to evict people from re-purposed medieval buildings. Despite this, Hampi Bazaar still sits right amongst the ruins of Vijayanagara and the transition from one into the other is seamless.

Hampi Bazaar, whilst by no means an inhospitable place, is likely not for those who are used to luxury – most of the hotels are very basic and some lack hot water and private bathrooms. Many hotel rooms are also quite musty and mouldy – a consequence of the humid conditions and walls apparently lacking damp protection from the earthy foundations. Yet it is a lovely place to stay – the colourful houses are intimately close together, and the local people can be seen getting on with their lives in the midst of the tourist hordes who inevitably fill this place.

It is especially popular with younger, more alternative travellers – some of whom come to Hampi and get stuck for days or weeks. It has a very chilled aspect to it and the many roof-top restaurants, despite the disappointingly average quality of the food across the board, are excellent places from which to view both the village and the surrounding landscape. The proximity of the torrential river makes the setting all the more idyllic and exotic.

As noted above, Hampi Bazaar has its fair share of ruins and intact medieval structures. The monumental Virupaksha temple, flanked by an epic cistern, seems almost embarrassingly oversized for the modest village. Yet this but a taste of the wide array of impressive structures and temple enclosures dotted around the huge site. The number of temples is astonishing and their intactness gives some parts of the site the sense of a ghost-town, hastily abandoned. It is possible to walk for hours, for days and still only touch on what is on offer here.

Following the river to the northeast leads one through a glorious landscape, past a fantastical collection of ruined complexes to the immense Vitthala Temple with its famous stone chariot – the wheels of which still turn. Though it is less than five kilometres, one could spend at least an entire walking there and idling back, exploring the temples and enjoying the natural setting.

The Royal Enclosure, to the south of Hampi Bazaar, marks the old centre of the medieval city. It is here that some of the most impressive monuments are to be found – such as the Lotus Mahal – said to be the queen’s pleasure palace, and the elephant stables. At least a day is required to satisfactorily explore this wide area, depending on your patience, curiosity and temperament. Either way, be prepared for a lot of walking, or else hire a motorbike or auto-rickshaw with driver as the massive scale of the site means many of these monuments are widely spaced.

Whilst the landscape seems, for the most part, dry, rusty and scrubby, it is full of bright green palms and banana plantations. The rich, dark soil of the flood-plains also yields brilliant, emerald green rice-fields which illuminate the dry, toweringly smooth rocks with radiant verdure.

It is a curious mix of the lush and the semi-arid, and can also contain some nasty surprises should one venture off the beaten track. Hard, sharp white thorns, up to an inch and a half long and strong enough to penetrate a rubber sole, often lie in the undergrowth. I learned about these the painful way, when I put my full weight on one in a pair of thongs and nastily punctured my foot which then spasmed awkwardly for the next two minutes. The thorn went so deep into my foot that it nearly came through the other side and for days afterwards walking was a very tender exercise.

Another place worth visiting is the small, historic village of Anegundi. It lies a few kilometres to the north east of Hampi Bazaar and, without taking an enormous detour, can only be accessed by ferry.

Construction of a bridge crossing at Anegundi began in 1999, but was halted the following year over concerns about the impact on the site, both physically and visually. Shortly after reconstruction was resumed in 2009, the bridge collapsed, killing eight construction workers. It now lies like a crooked slippery dip, angled into the river – an interesting modern ruin.

The local people remain with no choice but to take the tiny ferry or another, private boat, across. A few motorbikes can fit aboard the ferry, but cars are forced to drive some forty-odd kilometres to access the nearest bridge.

A local guy from Anegundi with whom we spoke on the ferry was very vocal, if philosophical about the bridge. It was corruption, he said – poor construction due to cutting corners. “This is an India problem,” he said. So it seems.

With such an unreal and captivating landscape, Hampi demands being seen at both sunrise and sunset. There are many vantage points which will yield a mind-blowing view, and the elevated places immediately outside Hampi Bazaar are some of the best. At these times of day the landscape’s colours are smoothed with an orange wash from the low-hanging sun. One morning, V and I set out before dawn to climb the rocky hill at the eastern end of the town. The wan light of morning was powerfully evocative of sunrise on another planet.

When we descended from the boulder atop which we had been sitting, we came across another temple site we had not found yet, nestled between hills and palm trees. The heaviness in my heart and guts was the heaviness of awe – weighty feelings of eternity and mortality, fuelled by aesthetic beauty and the visceral freshness of the early morning grandiose. For four days Hampi had me under its spell – it is not something I’m ever likely to forget.

You must be logged in to post a comment.