The demotion of Pluto as a planet back in August 2006 caused a great stir and left many people feeling disappointed.

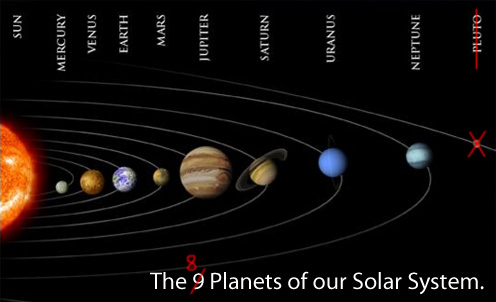

Since its discovery in 1930, several generations have been taught that there are 9 planets in the Solar System, no more, no less. Considering how sophisticated our knowledge of space and our own planetary system has become, it must have seemed as though this were a fixed figure, unlikely to change. After all, could there really be other planets out there that we had somehow missed?

Science fiction has made much of the idea of “the 10th planet,” yet with no other planets apparently introduced to the ledger since 1930, was it likely that any further planets were going to be discovered? And, perhaps more pertinently, what could possibly cause a planet to lose its status as a planet? What actually is a planet?

The answers to all this should excite anyone who has an interest in astronomy and offer more than mere solace to people mourning the demotion of Pluto. For, in recent years, many more planets have been discovered in our solar system – or, rather, many more “dwarf planets” have been discovered, and it was the discovery of another distant planet that is, in effect, larger and heavier than Pluto, that led to Pluto’s demise. Of course, Pluto isn’t going anywhere, not in a hurry, anyway, considering it takes 247.68 years to orbit the sun, but it now bears the status of “dwarf planet”, precisely because, if we were to accept it as a planet, we would have no choice but to welcome many more planets to the roster.

This in itself might not be such a bad thing, considering how little known most of the newly discovered planetoids / dwarf planets are, but the lengthy debates about what constitutes a planet did set out some sensible ground rules for planetary status, even if these rules remain hotly disputed.

Here’s how the International Astronomical Union defines a planet in our Solar System:

It is a celestial body which:

-

is in orbit around the Sun,

-

has sufficient mass to assume hydrostatic equilibrium (a nearly round shape), and

-

has “cleared the neighbourhood” around its orbit.

The first rule is clear enough – and, of course, we are talking about our own star, the Sun, or rather, Sol. The second rule is mostly obvious – in simple terms, a planet should be round. A fuller definition of hydrostatic equilibrium is as follows:

the object is symmetrically rounded into a spheroid or ellipsoid shape, where any irregular surface features are due to a relatively thin solid crust.

In other words, the product of things like tectonic forces, rather than simply being wildly out of shape. Earth is round (well, slightly ovoid) Mars is round and even Pluto is round. If it doesn’t look like a deformed potato – such as Mars’ moon Phobos – then it has passed the second hurdle of planet-hood.

Otherwise, we would simply designate it an asteroid or minor planet (explained below).

Not listed above, but best mentioned now because it marks the other boundary of planetary size and mass, is a further necessary rule of planethood – that it not be massive enough to cause thermonuclear fusion.

This simply means that a planet not be massive enough to ignite and form another star. Jupiter, for example, is a star that might have been – a failed star. With rather a lot of extra gas and mass, it may just have got there, but it didn’t. It’s a gas giant, not a star, precisely because it was “not massive enough to cause thermonuclear fusion. ”

Fair enough. Yet it is the third definition – having “cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit” that has proven the most contentious and, ultimately, made all the difference. The idea works like this:

In the end stages of planet formation, a planet will have “cleared the neighbourhood” of its own orbital zone, meaning it has become gravitationally dominant, and there are no other bodies of comparable size other than its own satellites or those otherwise under its gravitational influence.

In other words, if a planet is a planet, it must be the only object, apart from its moons, to follow the same orbital path – a lone car on an otherwise empty highway. Mercury does this, Venus does this, Earth does this, but Pluto does not do this.

If we think of the asteroid belt, the very name “belt” says it all. It is a space in which many objects share the same orbital path and no one object dominates with its gravity. Indeed, if one object did do this, then what would have to happen is that the objects in the same orbital path would have to be drawn together, colliding to form a new planet, or fall into orbit and become moons of the new planetary body which formed from the rest of the material.

The rules differentiating planets from dwarf planets are thus based on the following:

A large body which meets the other criteria for a planet but has not cleared its neighbourhood is classified as a dwarf planet. This includes Pluto, which shares its orbital neighbourhood with Kuiper belt objects such as the plutinos.

The Kuiper belt, incidentally, is a region of the Solar System beyond the planets which begins at the extremities of Neptune’s orbit. Neptune orbits at roughly 30 AU (1 Astronomical Unit = the distance of the Earth from the Sun) whilst the Kuiper belt extends as far as 50 AU from the sun. It is not unlike the asteroid belt, but it is much larger – 20 times as wide and roughly 20 to 200 times as massive. It consists of remnants from the Solar System’s formation – in other words, pieces of rock and ice of varying size which did not come together to form planets, or which did come together to form dwarf planets or minor planets – planets which then failed to achieve sufficient size and mass to clear their orbital path.

No doubt you’re also wondering what a plutino is. In effect, they are objects which are caught in a 2:3 mean motion resonance with Neptune. In other words, for every two orbits that a plutino makes, Neptune makes three. They share the same orbital resonance as Pluto and follow a similar path. Indeed, it was the discovery of the plutinos as much as anything else that led to Pluto’s demise. Pluto has not cleared these from its orbital path.

So where does all this leave us? The truly exciting answer is that we are left with a surprisingly large number of dwarf planets in our Solar System. Those which orbit beyond Neptune, in the outer Solar System, are included under the rubric of trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs). To our knowledge, there are no less than 620,000 TNOs, but before we get too excited about this figure, it must be said that this number is not for dwarf planets, but rather another categorisation: Minor Planets. Minor planets include dwarf planets, asteroids, trojans, centaurs, Kuiper belt objects, and other trans-Neptunian objects. Ignoring the other categories, let’s focus instead on how many dwarf planets have so far been identified in total, not just in trans-Neptunian orbits, though this is where most of them reside.

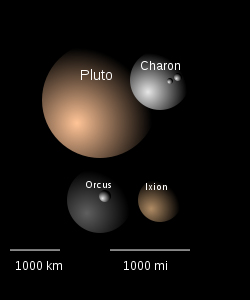

At this stage the IAU has definitively named five dwarf planets: Ceres, Pluto, Eris, Haumea, and Makemake. A further six, which in all likelihood are dwarf planets, have been discovered and await official recognition: Orcus, Sedna, Quaoar, Salaci and the less charmingly named 2002 MS4 and 2007 OR10. Another twenty-two objects have been identified which need further observation to determine whether or not they achieve dwarf planet status.

So, rather than a mere 8 or 9 planets in our Solar System, we may potentially include as many as 30 dwarf planets roaming around out there. I am deliberately ignoring the 19 moons in our Solar System, including our own, which are large or massive enough to achieve dwarf planet status (7, in fact, are more massive than Pluto: the Earth’s Moon, Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, Titan & Triton) yet which clearly fall short on account of their orbiting other planets and not orbiting the sun.

Incidentally, Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, is the only large moon in the solar system with a retrograde orbit – in other words, it orbits in the opposite direction to the planet’s rotation – and is almost certainly a Kuiper belt dwarf planet that was captured by Neptune’s gravity.

It is also worth noting that, as impressive as the number of dwarf planets discovered so far may be, the IAU estimates that there might be as many as 200 dwarf planets in the Kuiper belt alone, and, wait for it, anything up to 10,000 in the region beyond.

So what is beyond the Kuiper Belt? Well, remember how big space is, and here I am inclined to quote Douglas Adams: “Space is big, really big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mindbogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist’s, but that’s just peanuts to space…” Well, the solar system itself is also really big. The sun, an otherwise unremarkable star amongst billions, exerts an influence across a region that likely extends as far as 50,000 AU – roughly one light-year from the sun itself, though some are even willing to speculate that its influence extends loosely as far as 200,000 AU. The Kuiper belt is but a tiny narrow region by comparison to the Oort Cloud which surrounds and embraces the entire Solar System, as the image below makes clear. We shall talk about Sedna later.

Exactly what lies in the Oort cloud is anyone’s guess, though we needn’t assume it is anything alarmingly different from what we find in the Kuiper belt or asteroid belt for that matter. It is just another vast sea of rock and ice, and the likely point of origin for most comets which enter our inner Solar System.

Yet, I don’t wish to digress too far into the lesser known outer regions of the Solar System, which it is not feasible to explore adequately in the immediate future. Instead, let’s turn our attention to some of the exciting new (and not so new) dwarf planets that have been identified.

ERIS

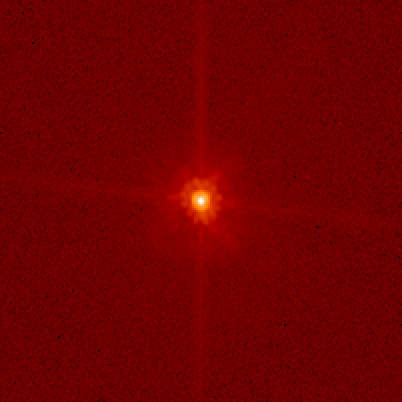

We must begin with Eris, which is, in effect, the key player in the drama surrounding Pluto’s demotion. It was with the discovery of Eris in January 2005 that astronomers decided they needed new rules for determining exactly what constitutes a planet. Eris is actually larger and heavier than Pluto. At roughly 2336 km in diameter and just over a quarter the mass of the Earth, it is by no means an insignificant little rock. On account of its size, Eris briefly earned the title of the 10th planet, yet it was precisely because astronomers expected to find further objects of similar mass and size that they decided new rules needed to be established before the number of official planets got out of hand.

Eris actually resides in a region called the scattered disc. This region covers much the same space as the Kuiper belt, yet scattered disc objects are characterised by their less stable orbits.

The distinction is not, however, clear cut and many astronomers include the scattered disc as part of the further reaches of the Kuiper belt. The orbit of Eris is typical of scattered disc objects in that it is highly elliptical.

During an orbital period of 557 years, its distance from the sun varies between a maximum (aphelion) of 97.5 AU, to as low as 37.9 AU (perihelion). In 2011, Eris was close to its aphelion at 96.6 AU, and will not return to its perihelion until around AD 2256. This eccentric orbit naturally affects the planet’s temperature significantly, though its distance from the sun is so great at the best of times that its range of temperature is estimated at somewhere between 30 and 56 Kelvin – ie. -243 to -217 degrees. Not very hospitable. Infrared light from Eris indicates the presence of methane ice on the surface, suggesting it is similar in some ways to Pluto. Eris appears to be grey in colour, though, like Pluto, it is far too distant to determine any surface features at this range, with our current technology. The artists’ impressions, detailed as they may appear, are merely approximations based on information gleaned from our knowledge of its mass, density, albedo (reflectivity) and the colour of light it emits.

It is unlikely that we shall get a close look at it in the near future, so holding your breath is not recommended. But we most certainly will, sometime in the next few centuries, if we don’ t destroy ourselves. Eris also has one known moon, called Dysomia, the name of the goddess Eris’ daughter, and also the ancient Greek word for “lawlessness.”

CERES

Our next stop on the New Solar System tour is Ceres – a dwarf planet whose presence has been known since 1801. Despite its not being a new discovery, Ceres has only recently been re-categorised as a dwarf planet and is unique in being the only dwarf planet in the inner Solar System. Being the largest body in the asteroid belt, it was the first object to be identified in that region and was originally designated planetary status, along with the asteroids 2 Pallas, 3 Juno and 4 Vesta – a status it retained for roughly 50 years.

The classification of Ceres is still somewhat unclear, with Nasa and various astronomy manuals continuing to refer to it as an asteroid, but then, the term asteroid has never been defined adequately and in many cases “minor planet” is used as a sort of umbrella rubric. So much for semantics. To all intents and purposes, however, Ceres is a dwarf planet. It certainly has a neat, round shape because its mass is sufficient to round it – rule 2 of dwarf planet status as outlined above.

Ceres may be the largest object in the asteroid belt – around 950km in diameter – and consists of roughly one third of the belt’s total mass, yet it is still rather small, consisting of roughly 4% of the Moon’s mass. That sounds pretty puny, but then, this equates to a surface area of 2,850,000 sq km – roughly the size of India or Argentina, which is actually pretty large.

Ceres is especially exciting to us on account of its proximity, composition and its relative warmth. Orbiting between Mars and Jupiter, its maximum surface temperature has been measured at around -38 degrees Celsius, a little warmer than parts of Canada in winter : ) The surface of the planet is likely a mixture of water ice and carbonates and clay minerals and the planet may have a tenuous atmosphere, along with water frost on its surface.

Because of its low mass and escape velocity, Ceres has been proposed as a possible destination for manned missions. Unlike Mars, where it would be extremely difficult to take off again, Ceres offers a much easier option for a crewed ship. Ceres has even been proposed as a possible destination for human colonisation – and also as a possible way-station for further exploration of the inner and outer solar system.

At this stage our knowledge of Ceres is fairly limited, but fortunately this is all about to change in March or April 2015 when NASA’s Dawn spacecraft arrives at Ceres. Dawn will initially orbit Ceres at an altitude of roughly 5,900 km and gradually reduce its orbit over a five month period to around 1300km. After another five months it will further reduce its orbit to a distance of only 700km. Equipped with cameras, spectrometers, gamma-ray and neutron detectors, Dawn is set to radically transform our understanding not only of Ceres itself, but of dwarf planets in general.

Launched in September 2007, Dawn has already spent more than a year in orbit around the asteroid 4-Vesta, which was, along with Ceres, initially recognised as a planet in the 19th century.

It is one of the largest asteroids in the solar system with a mean diameter of 525 kilometres and comprises roughly 9% of the mass of the asteroid belt. At 800,000 square kilometres, its surface area is roughly the size of Pakistan. Sadly for Vesta, however, it didn’t quite make the dwarf planet grade and remains an asteroid, terminologically.

MAKEMAKE

Next on our list is Makemake, a dwarf planet named after the eponymous creator of humanity and god of fertility in the mythos of the Rapanui, the native people of Easter Island. It is roughly two thirds the size of Pluto and has no known moons, making it very difficult to correctly estimate its mass. Makemake is considered another Kuiper belt object with an eccentric 310-year orbital period which varies in distance from roughly 38.5 AU to a maximum of 52.3 AU.

Makemake was another recent discovery – March 31, 2005 – and was officially recognised as a dwarf planet by the IAU in July 2008. Makemake is too distant to obtain detailed information or images and our best observations come from April 2011 when it passed in front of an 18th magnitude star. Makemake appears to lack a substantial atmosphere and its surface is likely covered with methane, ethane and possibly nitrogen ices. On account of its surface gases, Makemake might have a transient atmosphere much like Pluto when it nears its perihelion – ie, is closest to the sun. Like Pluto, Makemake also appears red in the visible light spectrum on account of the presence of tholins on its surface – molecules formed by irradiation of organic compounds such as ethane and methane, which have a reddish brown appearance.

The colour and albedo of the surface varies in places, giving the planet a somewhat patchy, spotty appearance.

HAUMEA

Named after the Hawaiian goddess of childbirth, Haumea was discovered in 2004 and recognised as a dwarf planet on September 17, 2008. It has two moons by the name of Hi’iaka and Namaka. Haumea is distinguished not only by its shape, but by its unusually rapid rotation, high density and high albedo – caused by a surface of crystalline water ice.

The surface colour and composition is considered peculiar – for its location the solar system, it should not have crystalline ice, but what is known as amorphous ice. This has led astronomers to assume that some relatively recent resurfacing has occurred, though no adequate mechanism has yet been proposed for this. A large dark red area on Haumea’s otherwise bright white surface was identified in September 2009, possibly the result of an impact. This suggests an area rich in minerals and organic (carbon-rich) compounds, or possibly a higher proportion of crystalline ice. Consequently, Haumea may have a mottled surface similar to that of Pluto, if not as diversified.

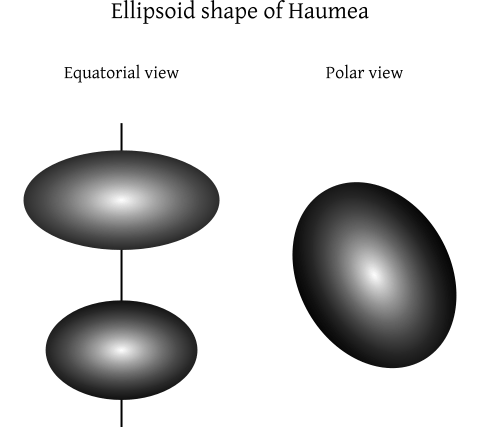

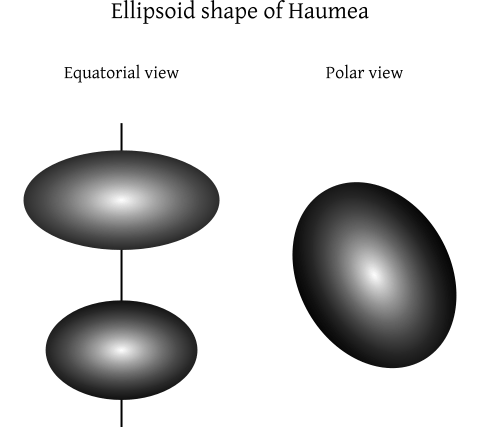

Haumea strikes me as an odd designation on account of its ellipsoid shape, as illustrated here.

Haumea’s shape has not been directly observed, yet it is inferred from its light curve, which suggests that its major axis is double the length of its minor. This may seem to challenge the definition of what constitutes a dwarf planet, yet it is considered to be in hydrostatic equilibrium – which, just to remind you, means : the object is symmetrically rounded into a spheroid or ellipsoid shape, where any irregular surface features are due to a relatively thin solid crust. Confusing, I know, but such is the nature of planetary classification. The shape and spin of the planet are thought to be the result of a giant collision.

Haumea’s orbit is not dissimilar to that of Makemake, following a similarly elliptical path ranging from 34.7 AU to 51.5 AU. Like so many of the dwarf planets, it is a frozen and forbidding place, though at least the presence of water ice offers some refreshment.

PLUTO

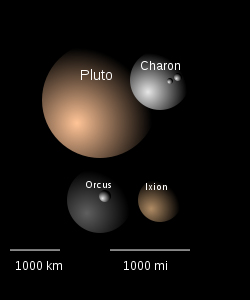

And last, but not least, let’s take a look at good old Pluto, a dwarf planet almost as mysterious as the others. Pluto is the second most massive dwarf planet after Eris and the tenth most massive body orbiting the sun. Composed primarily of rock and ice, it too has an eccentric and highly inclined orbit which, like many of the other TNOs, takes it from roughly 30 to 49 AU during its 248 year orbit. Pluto is exceptional among the other outer Solar System dwarf planets in that its orbit periodically brings it closer to the sun than Neptune. As of this year, 2014, Pluto sits at a distance of roughly 32.6 AU.

We have already discussed Pluto’s demise as a planet, yet the questions surrounding its status began as early as 1977 with the discovery of a minor planet designated 2060 Chiron, an early candidate for the much coveted title of 10th planet. Chiron was the first of numerous icy objects to be found in the region of Pluto, suggesting that Pluto might merely be one of a cluster of minor planets in the outer Solar System. The ultimate result of course, after the discovery of Eris, was Pluto’s demotion, yet still many astronomers argue that it should remain a planet and the other dwarf planets be added to the planet count.

Pluto, however, has a further major peculiarity – it has five moons by the names of Charon, Nix, Hydra, Kerberos and Styx – and rather than these neatly orbiting around Pluto, it exists in a kind of binary dance with its largest moon.

The barycenter of their orbits does not lie at Pluto’s centre, but between Pluto and Charon, rather like two dancers holding hands and swinging each other round, though Pluto remains very much at the centre of the dance.

The IAU has yet to distinguish between such binary dwarf planet systems and others, and for the moment, there is simply no distinction.

Our observations of Pluto have been very limited and only very unclear images exist of its surface. This, however, is about to change dramatically when, in 2015 (a great year for planetary exploration, woot!) NASA’s New Horizon probe will finally arrive at Pluto and perform a flyby. New Horizons will attempt to take detailed measurements and images of Pluto and its moons. When it has passed Pluto, New Horizons will attempt to explore the Kuiper belt, and astronomers have spent the last few years trying to find suitable targets within its flight path. Stay tuned.

What we do know about Pluto is that it has one of the most contrastive appearances of any body in the Solar System, with distinct polar regions and areas of charcoal black, dark orange and bright white. It has a thin atmosphere of nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide gases, which are derived from the sublimation of the ices on its surface. Like some of the dwarf planets already discussed, Pluto’s elliptical orbit has an effect on its atmosphere and surface pressure. Indeed, as it moves further away from the sun, its atmosphere is likely to freeze and collapse.

Like so many of the dwarf planets, which are extremely difficult to study directly, the size and mass of Pluto is based on best estimates. It is tiny compared even to the Earth, with a diameter of roughly 2306 km – around two thirds that of the Moon. It’s surface area is 16,647,940 km2 only 3.3% the size of Earth, and yet, when you consider that is roughly the size of Russia, it doesn’t seem all that small after all. Its mass, however, is significantly smaller proportionally at an estimated 0.24 % that of the Earth and, volume wise, around 18 Plutos could be squeezed inside the Earth. As mentioned above, Pluto is actually less massive than seven of the moons throughout the Solar System.

QUAOAR, ORCUS & SEDNA

So there we have it, a rough and ready tour of the new Solar System. There are other as yet unclassified dwarf planets that could be discussed here: little pale-red Quaoar – about half the size of Pluto with one pill-shaped moon with the enticing name of Weywot;

tiny Orcus, another Plutinoid about half the size of Pluto, with a similar orbital time and range, also sporting a single moon called Vanth

– and finally, perhaps the oddest of them all – bright red Sedna, whose extraordinary orbit ranges from c. 76 AU to 937 AU and takes roughly 11,400 years to make a single circuit.

It is the largest of these last three, though still just over two-thirds the size of Pluto.

Despite their almost certain classification as dwarf planets in the future, no doubt along with many others, until such a time I shall refrain from taking the liberty. As to their future exploration, I certainly hope I shall live to see more light shed on them. Considering the time and cost of preparing missions, the distance of the outer planets and the lengthy travel times, it might be decades if not centuries before these planets are better revealed or even visited. Fingers crossed it will happen sooner rather than later, if only to satisfy my vain curiosity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.