Well, I just turned forty. More than a week ago in fact, which is probably just enough time for the new reality to sink in. It was easy to be honest, all I had to do was stay alive and sure enough the day came along as so many others have done: roughly 14, 610 to be precise. But seriously, despite some inevitable reflection and re-assessment of my circumstances, I didn’t feel overly anxious or depressed about it. Indeed, I surprised myself by being relatively philosophical about the whole thing.

They say that forty is the new thirty, which is nice considering the old thirty was the new twenty, which makes me feel almost half my age. These days, with the cost of living in Australia being what it is, they say the fifty is the new twenty, and I can only hope this also applies to age, when that more ominous fifth decade begins.

Turning forty is one of life’s many arbitrary milestones. As with so many “significant” numbers – like the millennium or our birth dates – it has no actual importance and is merely a human conceit for the sake of record keeping and measurement. The number itself is meaningless, yet this will not stop people from weighing it down with vast amounts of baggage as it does, inarguably, represent a sort of rough half-way mark. There is a certain weightiness to the idea that as much as half of one’s life might already be over.

A quick scan of the accumulated ‘wisdom’ on the internet offers many different perspectives on turning forty. Some say it is a time when people begin to enjoy the hard work of their twenties and thirties, which is all very well if you actually bothered to work hard in your twenties and thirties. Others say that it is a time when men go off the rails with a mid-life crisis in an attempt to recapture lost youth. Again, that’s all very well if you let your youth go earlier and lived a responsible hard-working life to this point. It’s also said that most people have already come to accept responsibilities by this age: family, children, mortgage – what Zorba the Greek called “The full catastrophe!” – and have thus achieved a certain emotional and psychological stability. Again, “the full catastrophe” is something which has eluded me, along with learning to drive, superannuation and most forms of appreciable work experience. Still, after years of constant philosophising and, more recently, head-shrinking, I do feel more in control of my emotions and psychology, particularly in how I relate to people.

I’ve approached forty with the outlook that most people sport around thirty – namely that it’s time to “get serious”, whatever that’s supposed to mean. I’ve put off “getting serious” as long as possible, partly because it seemed so utterly undesirable, but mostly because there were other more fun things to do first. I’ve never had much interest in being responsible for other people, and only marginally more interest in being responsible for myself. Indeed, life, until now, with the exception of various bursts of zeal for some sort of stability and career, has been about maximising pleasure and experience. Ironically, however, outside the bouts of travel, study, freedom and self-indulgence, the status quo has mostly been a lot of unpaid hard work and agonising.

Throughout my late thirties, I often wondered what it would be like to turn forty. Indeed, I wondered about it so much that it almost felt as though I were hanging around waiting for it to happen. I put life on hold, lost myself in computer games and travel, indulged in writing and photography as hobbies rather than commercial ventures, worked part time and lazed my way along. I needed a deadline of sorts, or rather, a starting line, beyond which point I must work hard to secure the future I wanted to have. But what was that?

Having dreaded the idea of turning forty for so long, when the approaching reality finally began to loom, I switched tack and started to see things more positively. Quite simply, it was a decision I made, having grown tired of carrying around a gloomy outlook. Where, I ask, does that get you? There’s nothing wrong with a little righteous indignation about the world, but who wants to go through life whining and complaining, especially about one’s personal state of affairs, when a little positive thinking can make life far more pleasurable? “You always take the weather with you,” and whilst I’ll always love the rain, of late I’ve been toting sunshine.

I’ve never really wanted to be rich, but then I’ve never really wanted to be poor. When I turned forty I knew I must begin to say yes to settling down, partly because the old paradigm of freedom wasn’t working so well any more. Despite my love of restless roaming through life, the lack of grounding has taken its toll in constant exposure to the anxiety of uncertainty. Whilst in many ways it is easier to remain aloof in life, it requires a singular energy and confidence to do so. Consequently, while many at this age are rebelling against their early establishment of security, I have gradually been developing a longing for its sense of permanence.

This longing for permanence has finally begun to take shape. I knew something was changing in me when I began to answer the question of children with “well, I don’t want not to have them,” instead of the requisite “screw that.” This change has occurred in the last eighteen months – indeed, as recently as February 2011 I reaffirmed my desire not to have children in the only piece I’ve ever pulled from this blog. It was written in response to the news that the partners of two of my oldest friends were newly pregnant, which caused me to take a good long look at where I stood in the world. I had meant the article to be light-hearted and entertaining, but when I re-read it some months later, it came across as awfully mean-spirited and so I pulled it.

My principal concern then was the loss of freedom:

Would I ever see a film at the cinema again? Could I ever just clear off to India for two months as I did last year? Would I ever sleep again? I plan to cling to my bachelor existence as long as humanly possible. If that means for the rest of my life, then so be it and here’s to me. Let’s face it, someone’s got to do it.

It’s a very reasonable concern given the way in which the lives of my friends with children have been transformed. Yet of course, on another level, it also reflects a rather trivial shallowness. Selfishness I can accept as a motivation, but the conclusion that life is only meaningful or satisfying when free of responsibility is not self-evident.

So, turning forty was, in the end, absolutely necessary and couldn’t have come a moment too soon. Indeed, it was a relief. I have had difficulty throughout life in understanding what age I actually was at the time and knowing what was expected of me at that age. This is largely because I long remained infuriatingly childish and didn’t give a rat’s arse about what was expected of me, and indeed, resented anyone who had the audacity to expect anything from me, but also because I spent fifteen years at university. The world of work and careers and suits and responsibility may have its merits, but it seemed far more interesting to stay in school indefinitely having wonderful romances, challenging conversations and intellectually decadent junkets. For my twenties and thirties, the motto was always “when in doubt, do a degree.” And I can say this much – I fucking loved it.

Spending so much time at university left me at odds with the professional world. My peers were always students – aspiring writers, academics, scientists and historians – and so I was largely insulated from the working world and found it all rather distastefully vulgar. The apparent drudgery of a stressful Monday to Friday job compared to sitting on the banks of the Cam drinking Pimms and talking about the fall of the Roman Empire, was so gut-wrenchingly unappealing that I vowed to do everything I could to avoid it for as long as possible.

Yet of course, this was a vow made with a different energy and a different psychology. Things changed, in part, when my age caught up with me at last. When I was thirty-five, everyone looked at me and thought I was thirty. When I turned thirty-seven, everyone thought I was… thirty-seven. I took a look at myself in the mirror and saw that despite running regularly, doing weights and paying at least some attention to my diet, sufficient to keep my body in shape and my face lean, the wrinkles of worry and anxiety had gradually accumulated around my eyes. My hair was peppered with grey at the temples and my eyebrows had a certain mature bushiness. I took this template of selfhood with me and held it up against the men on the street. My gods, I thought, when I realised who my peers were. They look like the dads in mortgage commercials, and so the fuck do I.

At least I still have my hair, and a wonderfully thick and full-bodied covering to boot. And while I am slowly but surely revealing my deep and abiding vanity here, I might as well go on to say that I have always equated hair with youth. If I ever lose it, I will go straight to Advanced Hair and pay whatever it takes to get it back. Baldness is not an option and I dearly hope to be sporting a Bob Hawke silver bodgie when I reach the dear old age of one hundred and twenty. So, from a purely physical point of view, having reached forty, I look just how I always wanted to look at forty. That’s quite a relief.

Having said all this, I still feel largely out of place in the world. It never ceases to amaze me that people I went to school with have serious jobs, own houses and cars, and heaven forbid, have children as old as ten. How on earth did they manage it all, and why did they want to do so?

A week before my birthday, whilst walking to a restaurant with my father, he displayed his special brand of tiresomely contrived surprise when, in response to his question, I told him I was turning forty.

“Forty! Forty! Mate, you can’t be turning forty.”

“Do the maths.”

“Forty! Jesus, mate, when I was forty I’d already had three sons and two marriages. I was a top journo at the Australian.”

“Well, I’ve got three degrees including a PhD from Cambridge.”

“Stuff that mate, they’re just pieces of paper.”

“Fuck you.”

“Mate, I was just joking.”

But of course he wasn’t, and of course, I didn’t give a rat’s arse either. I’m pleased to have found my own way to forty, and whilst the next decade might prove to be ostensibly more conventional, I can assure you I shall be doing it in my own idiom.

Posted in Memoir, The Odyssey of Life | Leave a Comment »

After the high times of the Cold War, the space race has gradually slowed to a crawl. The vast cuts to NASA’s budget – from an extraordinary peak at 4.41% of the Federal budget in 1965 to an estimated 0.48% in 2012 – and the cancelling of the shuttle program before the completion of a replacement reusable launch vehicle, have left them dependent on Russian rockets or the nascent private space industry to ferry personnel to the International Space Station. While China and India might be making bold strides with their own space programs, those grandiose, twentieth-century visions of the future, outlined in such classics as 2001: A Space Odyssey, seem quaintly naïve in retrospect. Without the budgets or political will of the initial Space Race, human exploration, or indeed, colonisation of the solar system remains a far-fetched and distant possibility.

Science fiction has long provided examples of human exploration and colonisation of other planets and moons and, indeed, other planetary systems and galaxies. This idea has been around since before the origins of space-flight. More often than not, the time frame for these ventures has seemed utterly implausible. Consider the glittering visions of the Atomic Age, with vast space-liners and freighters ploughing the atmosphere over towering futuristic skylines – a future expected to arrive as soon as the 1980s.

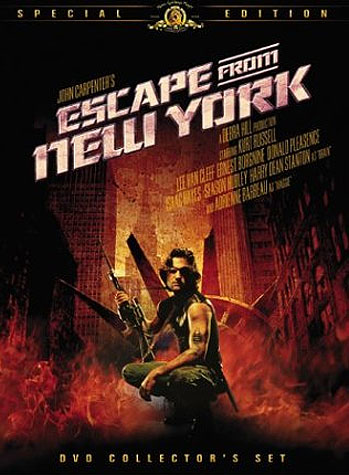

Even when our visions were darker and dystopian, apocalyptic futures were predicted – Orwell’s 1984, Harry Harrison’s More Room, More Room, or the film Escape from New York – the future was always too close.

The 1983 film Bladerunner,which presented a world of flying cars and sophisticated androids, suggested that humans were leaving in droves for the off-world colonies. It was set in 2019, a date which will come and go without even a hint of an established human presence on another planet.

More recently, the 2010 film Avatar posited a mining operation on the habitable moon Pandora in the year 2154. Even this still distant date seems preposterously optimistic. We might, by then, see humans active on other planets, moons, dwarf planets or asteroids in this solar system, but travelling beyond even the heliopause, let alone to bodies orbiting another star seems highly implausible.

The journey times and our lack of a near light-speed propulsion system, nor craft designs that can withstand such stresses, is likely to ensure such ventures remain in the realms of science fiction. Currently the fastest speed achieved in space for a crewed vehicle is 39,896 km/h, and 252,792 km/h for an un-crewed vehicle. The VASIMR plasma propulsion system, which has been in development now for four decades, is touted to be capable of achieving speeds of up to 600,000 km/h, which would significantly reduce journey times – reaching Mars might be a matter of weeks instead of the standard six to ten months.

Yet, considering that even the nearest star is 4.2 light-years away, the fastest possible journey time would be 4.2 years – and then only if we could achieve light speed – ie. 1,079,252,848.8 km/h. As much as I admire human ingenuity, this seems a nigh impossible prospect. Braking alone would be one hell of a job.

Some will say it is short-sighted to dismiss the possibilities of the incredible technologies that will no doubt be available in the coming centuries. Yet until we overcome the very significant problems of cost, distance, radiation exposure, physical deterioration in zero or low gravity, delayed communication, psychological stress and a whole host of other issues, there seems little chance of humans prioritising efforts to leave our own solar system in the next couple of centuries.

Looking closer to home, these very same problems are sufficient to make the colonisation and exploitation of our own solar system significantly difficult, if not unsustainably impossible in the long run. The first question that needs to be asked when considering the possibility of a human presence on other worlds is why go? There are, of course, many reasons why humans might choose to do so. The restrictions and limitations of Earth-based observatories, for example, have already led to the positioning of telescopes in space for better observations of the universe. Astronomers have long suggested that the moon would be an even better place to locate far larger and more sophisticated observational instruments, and this is certainly a viable long-term option. Whether or not such a facility would be crewed is another question altogether, though this would likely be an unnecessarily expensive extravagance.

The sheer cost of simple space exploration is already too great a disincentive to justify sending people for scientific purposes alone. The long-proposed crewed trip to Mars is now off the books at NASA and most experts think at best a time-frame of thirty to forty years is plausible for such a venture. The 2.5 billion dollar budget of the Mars Science Laboratory, better known as the Curiosity rover, is, for now, the last grand project NASA has planned for the solar system. The money simply is not there any longer.

A more economically viable reason for expanding human activity in space is tourism. Humans have already proven that they are willing to pay as much as twenty million dollars to go briefly into space on a Russian rocket, and already a ticket has been bought at a cost of 150 million dollars for a proposed circuit of the moon four years from now.

The incredible sights of the solar system – the mountains and canyons of Mars, the ice fountains of Enceladus, the volcanoes of Io, the turbulent storms of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, the ethane and methane lakes of Titan, the curious dance of the binary dwarf planets, Pluto and Charon, the towering ice cliffs of Dione to name a few, could one day make a very tempting grand tour for the mega, or perhaps, the meta rich.

Yet even journeys to destinations in the inner solar system, Venus, Mercury and Mars, would still require very great improvements in our spaceship building and life-support capability.

There is also the consideration of the long-term destiny of the human species. We know that in roughly five billion years our star, Sol, will swell to a vastly greater size and engulf the inner planets in its flatulent death, burning away what remains of the Earth’s atmosphere and oceans and ultimately, the planet itself. If we hope to continue to exist indefinitely, then irrespective of how unimaginably distant this date with planetary death might be, we have no choice but to find a new home. This, however, is hardly a priority at the moment.

If human colonisation is ever to take place, it will likely happen on a very, very long and slow timescale. Consider even the easiest option – a colony on the moon. It would take years just to establish the first structures on the surface, which would no doubt have to be very utilitarian. The moon has a cycle of 14 days of sunlight and 14 days of night, making solar power an unlikely prospect for energy. It is lacking in water and important volatiles such as argon, helium and compounds of carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen, leaving humans at the mercy of Earth resources for life-support and construction purposes. Structures might be pre-fabbed in space and somehow landed on the surface, yet even this would challenge our current engineering capacity. Perhaps our best parallels are the scientific bases in Antarctica, though even building something as sophisticated as these would require incredible engineering and vast sums of money to get the materials and labour to the moon. And some bloody huge rockets.

Having established even a tiny presence on the moon, we must then ask, how long before these colonies grew into anything beyond a scientific or industrial outpost? If there were to be any sort of recreational facilities, then this would require staffing and all manner of supplies that would need to be replenished on a regular basis. What would it cost to establish a cocktail bar on the moon, a hotel, a sauna and spa, a beauty salon? Who would go to work these jobs, and how would the facilities ensure safety, psychological stability, provide medical services and so on? Would there be much satisfaction in living in what would initially be a very small, claustrophobic community with limited recreational possibilities? There would no doubt be many customers wishing to get married on the moon, spend a honeymoon there, experience the incredible sight of the Earth-rise, yet one can see from this brief discussion that the business of providing the facilities and services would likely be expensive beyond all imaginings and take years to establish.

It is by no means impossible that space-tourist dollars will be sufficient to drive such developments, and I wouldn’t rule out a permanent human presence on the moon by the end of this century. NASA, of course, is not the only player in the game and increasingly the space programs of other nations are making impressive leaps forward. In 2008, India sent a space-craft around the moon and plans to send a satellite to orbit Mars in the coming year. China has made its ambitions clear with its vigorous and successful efforts to put people, Taikonauts, into space. Their incredible and centralised industrial capacity might reach such heights in the next few decades that building interplanetary craft will become simply another production-line process. Yet such a program would require an incentive far greater than mere prestige.

Japan, Russia, Iran and the European Space Agency also have sophisticated space programs and long-term ambitions for either scientific exploration, satellite deployment, industrial exploitation and, potentially, human colonisation, yet it is unlikely that any of these national programs will be building space bases on other planets, asteroids or moons any time soon. Unless they can justify the costs, and, indeed, find the capital in the first place, it seems the only types of enterprises that can sustain themselves in the long term are those that are capable of generating profit – and those profits will need to be as colossal as the venture itself.

Despite the apparent caution of the above, I believe that humans are, at last, on the cusp of expanding their activity and presence in the solar system. On May 22nd this year, SpaceX, the private company founded by Elon Musk, the man behind PayPal and the Tesla Roadster, successfully launched its Falcon 9 heavy payload rocket carrying another SpaceX vehicle, the Dragon Capsule, to the International Space Station.

It is difficult to downplay the significance of this achievement. Private operators have finally proven that they too can not only design and launch space vehicles, once the preserve of national governments, but they can build and design the entire craft themselves. NASA, on the other hand, has always relied on contractors to make some of its components. That private enterprise has the wherewithal to equal and potentially better even NASA’s achievements is evident. Exactly where that leads is another question.

A quick search of private space companies on the web will throw up an ever-lengthening list of businesses: Orbital Sciences Corp, Scorpius Space Launch Company, Interorbital Systems, Armadillo Aerospace, Blast Off! Corp, MirCorp, Space Adventures, ARCA and Galaxy Express, are a few hastily chosen examples in no particular order. Some companies have less ambitious plans – focussing solely on the design of rovers or propulsion systems, but others have grander designs of providing entire space-craft capable of fulfilling a variety of different roles. A company such as SpaceX, now firmly established as a contractor to NASA, has clear potential to develop and provide further bespoke craft for a variety of different purposes. It is likely just a question of time and money before we see more sophisticated vehicles being designed according to demand, be they in the service of tourism or heavy industry.

As things stand, it is this first category, tourism, which is behind much of the new enthusiasm for private space ventures. Virgin Galactic is now firmly focussed on its program of providing short, sub-orbital space-flights in its Spaceship 2 vehicle, for roughly $200,000 a ticket.

Should the venture prove to be as successful and profitable as is predicted, then no doubt Virgin Galactic will look to expand and upscale its operations.

Other companies will almost certainly join this race into low Earth orbit to cater for wealthy joy-riders who wish to experience zero gravity and see the Earth from space- albeit, very briefly.

Space tourism has, in fact, been with us for some time already. Between 2001 and 2009, Space Adventures offered flights to the International Space Station aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft for a price of between $20 and $35 million US dollars.

With the increase of the crew size on the ISS in 2010, the program was halted, but is expected to resume in 2013. As mentioned above, plans are afoot to offer two space tourists and a pilot the chance to do a 10-21 day moon flyby for roughly $100 million per passenger; the longer trip would include a visit to the ISS.

Tourism certainly has the potential to drive the space industry forward in future years, yet whether or not this will lead to the development of tourist resorts and facilities is another question. Will we see a hotel built in Earth orbit sometime in the coming decades? Perhaps one might be placed in orbit around the moon, or indeed, on it. Yet again, the many difficulties of building, staffing, supplying, maintaining and funding such a venture safely will be prohibitive, though by no means impossible.

One reason space ventures are so expensive is the cost of putting people there safely. The capacity to carry even a single person on a craft radically changes both the design and scale of the vehicle. Robots and probes do not require food, oxygen, hydration, sleeping quarters and waste disposal for example, and nor do they need to come home when their mission is completed. One of the biggest obstacles to a crewed mission to Mars is designing a ship that can not only reach the planet safely with a human crew, but still have sufficient thrust to leave the surface once done there. Mars may only have one third the Earth’s gravity, but on account of its mass, it has roughly 45% of Earth’s escape velocity. This means that to leave the surface of Mars, we need a rocket almost half the size of the rockets required to blast off from Earth, and the rocket that blasts off from Earth needs to carry such a rocket in the first place, meaning it would have to be a very, very large rocket indeed. The Curiosity rover, of course, only needs a one-way ticket.

All of this is, however, academic. Until we come up with a real incentive beyond mere prestige for sending humans instead of machines into space, the costs are too difficult to justify. Tourism might just be that killer app, as it were, yet, as it stands, the only other truly affordable incentive for going is the profit-driven pursuit of resources.

The idea of exploiting the vast mineral resources of the solar system is nothing new. Science fiction has offered countless examples of mining operations on distant planets and asteroids. The 2009 movie Moon, for example, posited a largely automated strip-mining facility on the moon, staffed by a single clone, which collected Helium 3 from the surface and shipped it back to Earth, allegedly accounting for almost 70% of the planet’s energy needs. Helium 3 is very rare on Earth but is more common on the moon – embedded in the upper layer of regolith – and has long been proposed as an energy source for new generation nuclear power plants. Whilst the potential of Helium 3 is largely speculatory, the idea of mining the moon is less so; it also contains commercially valuable deposits of iron, titanium, silicon and aluminium, for example. Yet there are other, perhaps easier and more profitable targets.

Consider these figures. In his book Mining the Sky, John S. Lewis suggests that an asteroid with a diameter of one kilometre, with a mass of around two billion tonnes, of which there are roughly one million within our system, would contain something in the realm of 30 million tonnes of nickel, 1.5 million tonnes of cobalt and 7500 tonnes of platinum.

The value of the platinum alone would, at current market value, be more than $150 billion USD. A NASA report estimated that the mineral wealth of all the asteroids in the asteroid belt would exceed $100 billion for each person on the planet (based on a population of 6 billion). The asteroid 16 Psyche is estimated to 1.7×1019 kg of nickel–iron, which, at current rates of consumption, would meet the world’s demands for several million years. Such an abundance could, ultimately, sink any such ventures. If the market was suddenly flooded with platinum, for example, the value of the metal might be significantly reduced. This would be just one of many significant economic risks involved in asteroid mining.

There has been a lot of talk about reaching peak oil on Earth, but other elements essential to modern industry might one day be in short supply. Worst case scenarios suggest shortages of important resources such as zinc, silver, tin, lead, gold, indium, antimony and copper within 50-60 years. Through methods such as spectroscopy and the study of meteorites, asteroids are also known to contain other very valuable elements such as cobalt, manganese, molybdenum, osmium, palladium, rhenium, rhodium, ruthenium and tungsten. Considering that all these elements originally arrived on Earth from asteroids and comets during the planet’s formation and the period known as the Late Heavy Bombardment, it seems appropriate that we should again look to asteroids for these important resources. Just how we will achieve such a feat, however, remains the pivotal question.

To begin with, we would need to build and design equipment capable of mining an asteroid and shipping the material back to Earth. Then we would need to get it to the asteroid. The actual method of mining might vary according to the asteroid’s composition; they might be strip-mined, shaft-mined or perhaps material could be collected magnetically from the surface. Due to their relatively low mass, asteroids have almost zero gravity, meaning that any equipment would need to be somehow tethered to the surface. Depending on the mining methods used, debris would likely float off into space, for better or for worse. The process of mining would need to be almost entirely automated as a human presence would require a whole new level of commitment and industrial engineering. Yet, without a human presence, any mechanical failure would be extremely difficult to fix, even by remote and robotic means, on account of the distance and delay in communication.

There is also the problem of collecting, refining, packaging and transporting the material back to Earth. How this would be done is anyone’s guess. Would we need an endless store of rockets to shoot the minerals back to Earth? Could they be somehow bundled and flung into Earth orbit, or to the moon for that matter, then collected and transported to the surface, perhaps by the long-dreamed of space-elevators? Would it be possible to transport asteroids into orbit around the Earth or moon where they might be more easily mined by both humans and machines?

When we begin to ask all these questions, the problems seem almost insurmountable. Yet, the lure of such vast profits has already seen the formation of three companies with serious proposals to mine asteroids. In November 2010, for example, the company Planetary Resources was founded, with the very serious intention of mining asteroids. The company, whose backers include director James Cameron and Google’s chief executive Larry Page, has already deployed its first bar-fridge sized ARKYD 100 “Leo” space telescope for prospecting purposes, and intends to deploy as many as ten to fifteen over the next few years.

As they say on their website “There are no roads where we’re headed. But we have a map.” This map will significantly improve as their telescope deployments increase and the company is able to identify their optimum targets for mineral exploitation.

Despite the apparent boldness of the venture, the idea of moving asteroids closer to the Earth might ultimately be the best means of gaining access to their wealth. Indeed, in a recent interview with the New Scientist, a Planetary Resources spokesman stated that:

One of the ways that we could do that is simply to turn the water on an asteroid into rocket fuel and burn it in a thruster that nudges its trajectory. Split water into hydrogen and oxygen, and you get the same fuels that launch space shuttles. Some asteroids are 20 per cent water, and that amount would let you move the thing anywhere in the solar system.

With the asteroid in orbit around the Earth or moon, journey times would become a matter of hours or days and allow much easier access for personnel. It would also make it far easier to make this a permanently crewed operation, and reduce to a manageable minimum any lag in communications.

The water content of the asteroids could not only be used to enable their propulsion, but used to produce rocket fuel to refuel craft in space. Indeed, the company aims to construct a fuel depot in Earth orbit by 2020 which could refuel commercial satellites or spacecraft. How soon they will be able to begin the process of creating the fuel from an asteroid is another matter altogether, but for now it’s a case of full steam ahead.

Whether or not asteroid mining proves to be cost-efficient could, to a very great degree, determine the future of human exploration and, potentially, colonisation of the solar system. Our ability to extract and refine material from other planetary bodies will be absolutely central to any attempts to establish a human presence elsewhere than Earth. The solar system is littered with asteroids, moons and dwarf planets that are rich enough in resources to sustain a permanent human settlement. Indeed, the long list of candidates for possible future outposts includes the Martian moons, Phobos and Deimos, the Jovian moons Europa, Callisto and Ganymede, the Saturnian moons Titan and Enceladus, and even the moons of Uranus, Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, Oberon and Triton. Perhaps the most suitable option might prove to be the dwarf planet Ceres, which is the only dwarf planet in the inner solar system and the largest body in the asteroid belt. With a diameter of roughly 950km and a surface area of just under three million square kilometres, it is almost exactly the same size as Argentina. The surface of Ceres is likely a mixture of water ice and hydrated minerals such as carbonates and clays. It appears to have a rocky core and icy mantle and may also have a subsurface ocean of liquid water. The highest measured surface temperature is roughly -38 celsius, making it relatively warm for such a distant body. The planet is also believed to have a very thin atmosphere.

One of the great advantages of Ceres is that, despite being further from the Earth than Mars, it is, in effect, easier to reach on account of its slower orbit and thus shorter synodic period – roughly 1 year and three months compared to Mars’ 2 years and 1 month. In other words, the Earth catches up to Ceres every fifteen months or so, whilst Mars is harder to catch, and the two planets are in opposition only once every two years. With more frequent launch windows and the far lower gravity of Ceres, it would be considerably easier not only for traffic back and forth, but require far less energy to launch from its surface than from the surface of Mars. Ceres has long been proposed as the best location for a human pit-stop and refuelling station from which to explore the outer solar system, and, indeed, to mine asteroids in the surrounding belt. In 2015, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft will arrive at Ceres for a much closer look and many interested parties are waiting keenly for the wealth of detailed information we expect to receive about the composition of this dwarf planet.

So it would seem that we might be at last on the brink of the long-expected expansion of human activity in the solar system. I suspect things will develop very slowly and no doubt there will be many set-backs and delays, yet the momentum is at last gathering not only for human exploration of the solar system, but potentially for the exploitation of its vast wealth of resources and, possibly, in the very long term, its colonisation. If humans can get all the resources they need to sustain their industrial capacity from space, and, possibly, their fuel and energy into the bargain, then this would very significantly reduce stresses on our own planet and potentially enable a far greener future. I’ll believe it when I see it, but I do feel at last somewhat confident that I will eventually see it.

Posted in Environment & Science | Leave a Comment »

Recently, my interest in online social networking has waned considerably. For a while now I’ve been questioning the motive behind expressing my feelings, desires and frustrations, or simply providing factual information about where I am and what I’m doing at any given point. I have, of late, been tweeting and updating Facebook much less frequently, and have completely failed to jump on the Instagram / Foursquare bandwagon. This seems slightly ironic considering the fact that after several years of wanting one, I finally acquired a smart-phone two months ago and thus have the capacity to be connected at all times.

There are, of course, many reasons for participating in social networks and people use them in a variety of different ways. Whether it is to maintain contact with friends, to make new friends, to pursue romance and sex, to promote themselves or their business, or simply because they can’t resist telling everyone everything about their life, people the world over are using social networks in ever increasing numbers and are likely to continue to do so.

Recently, sitting at a bar in Melbourne with my girlfriend, V, I realised that, despite being on holiday in another city, and despite doing a variety of different and exciting activities, eating great food, visiting galleries and museums, seeing quality exhibitions, going to a variety of cool bars and cafés – precisely the sort of thing people often tweet or update Facebook about – I had not once tweeted nor updated Facebook. For those of you out there who have never felt the urge to join Twitter or Facebook, this will all seem perfectly natural, yet for those of us who have been on social networks for some time, it’s the life-logging equivalent of a black hole.

I started talking to V about this as we sat drinking a most excellent local, cloudy cider in a new joint on Brunswick Street, and her first suggestion was that I didn’t feel the need to share everything because I had someone to share it with already – namely, her good self. This seemed to hit the nail right on the head, and it got me thinking that actually my waning interest in sharing such personal information and experiences was in large part due to being in a relationship. Was this really the sole, or, at least, principal reason? I doubted the former, but had to ask myself the questions: why, after all, did I join social networks in the first place, and what purpose did they serve in the present?

I suppose I got a taste for it from playing World of Warcraft. Despite only playing the game for a couple of months in mid 2006, the random connections with people the world over and my experience of the collective power of in-game Guilds was both eye-opening and intimidating. As a shy person, new to the game, I suffered the dreadful fear of being a noob and being seen to be such by other, more experienced players. Yet, shortly after joining, I realised that actually most people were pleasant enough and perfectly willing to help or give advice. I must have got lucky, I suppose, knowing in retrospect how many trolls inhabit the average game server these days. Either way, I came away from World of Warcraft loving the idea that I could connect with people the world over and have fun with them, even if the exchange was not necessarily meaningful. Being single at the time, living in a foreign city where I had as yet made few local friends, this was an attractive and easy way to have company.

It wasn’t long after this that I joined MySpace, to which I was introduced in late 2006 by work colleagues at the Corn Exchange theatre in Cambridge. My first inclination was to deride MySpace as a shameless vehicle for self-promotion and egotism, but reserving judgement publicly, so as not to risk having to eat my words later, I tried to be more open minded about it and soon found it rather inviting. What ultimately drew me to MySpace was, ironically, the shameless egotism of it. It seemed like a fun idea to have an online profile which somehow reflected the Me that I liked and allowed me to present myself to the world in what I considered a cool, flattering yet also slightly ironic, self-deprecating manner. I also joined because it enabled me to connect with my colleagues and have fun with them at work in a new and interesting way.

In truth, beyond these rather self-serving motives, I couldn’t see very much point to my MySpace page. After all, the people I was primarily connecting with were those I sat next to at work. I did, however, get a buzz from being able to be friends with He-Man, James Bond and Monkey among many others. Back then MySpace didn’t make it at all easy to customise one’s page, post a photograph, or anything for that matter. Indeed doing so involved copying long lines of code into the appropriate field, which required a MySpace code-generating program of some variety. I liked having a few friends on MySpace, and I enjoyed recruiting a couple of old friends in Australia in order to make contact with them easier and more fun, and yet, it didn’t actually make contact much easier. In fact, it was still easier to contact people via e-mail and most of my friends weren’t especially interested in setting up a profile. Fair enough.

Indeed, e-mail still remained the principal means of contacting my friends and family in Australia. I have written elsewhere about my diarising – having kept a diary and not missed a day since the age of 13 – and, as a writer, I always liked to try to entertain people by sending an occasional e-mail to my closer acquaintances, describing recent adventures. It served a dual purpose: putting my life into a narrative context, and, ideally, entertaining my friends and maintaining a dialogue with them.

The last of such group e-mails was sent earlier that same year, in 2006, and the following year I edited them as appropriate and posted them on this very blog. No doubt it would have been easier to start a blog sooner, and I probably should have done so years before, yet I still felt a desire to conduct the conversation in a more private manner, and also to try to keep, in my mind, the sense of unity amongst my friends – most of whom I was now very far away from. A group e-mail would often provoke a lot of responses and it felt like the nearest thing to seeing all these people at a party – something I could not otherwise do.

I can’t deny that the motivation to tell people what I was up to was also largely egotistical – something discussed in more detail below. Perhaps I needed people to recognise that I was living a good life, an adventurous life – no doubt largely on account of my innate sense of failure so far as my two chosen career paths were concerned – namely academia and creative writing. Yet, I’d always been a terribly loud person at parties who liked to entertain – was that due to some form of extroversion, or the explosive, drug and drink inspired bluster of the introvert? Either way, I had long wanted to be the entertainer in groups and tried to play that role, with, it’s fair to say, a degree of success.

I first heard of Facebook when I started dating an American geneticist who had been invited to join by many of her university colleagues in the States. Yet it wasn’t until after we had parted ways, around April of 2007, that my friend Georgina, who was also on MySpace – and World of Warcraft for that matter – told me after a brief trial that she found Facebook to be far superior to MySpace. Not only was it a great deal easier to create and update a profile, it was also far more interconnected than MySpace, with the ability to tag things and thus create hotlinks between profiles. This interconnectedness seemed, at the time, quite revolutionary, and I instantly took to Facebook like a duck to water. Once I was hooked, line and sinker, I fired off e-mails to everyone in my address book, inviting them to join. This recruitment drive was far more successful than my MySpace recruitment efforts, and, within a couple of months, the new arrivals having similarly spread the word, almost everyone I gave a shit about was on Facebook. There were, of course, a rare few who remained for a long time reluctant, and who still shun joining any social networks of any kind, and sure enough, I lost touch with them after that. Oops.

Once I had a large network of friends – and on Facebook, to begin with, I was only friends with actual friends – I found myself using the site constantly as a means of staying in touch. It was, of course, satisfying for many reasons – reconnecting with people, catching up on news, sharing something amusing and generating an entertaining discussion. It was also fortunate that the people in my age-group – mostly mid thirties – were mature enough not to participate in any trolling or bullying and so the interactions were almost universally carried out in a dignified and courteous manner. Though, of course, there was the occasional lewd and inappropriate comment to add some spice to the mix. It was also pleasing to see how many people got together back in Australia as a result of Facebook. I felt rather envious of their ability to hook up in person so easily, and in truth, it likely would not have happened without Facebook or another similarly easy to use social network coming along.

When I finally returned to Australia, I was certainly in a better position to catch up with people and knew how to get in touch with them. And this remains the very best aspect of Facebook: it is the ultimate address book. Whilst some people come and go, switching their profile off for a while, most people remain pretty firmly on Facebook. And even those who do turn off their profiles often seem to pop back on at some point and rejoin us. So, full marks for connectivity, and for ease of contact and access. These days the only e-mails I send are for professional reasons or to my parents, who haven’t quite made the leap into the ageing present, for better or worse.

So there I was in Melbourne wondering why I was no longer very interested in trying to entertain people on Facebook or Twitter, nor feeling any inclination to share my adventures and experiences. Had I finally begun to feel self-conscious about talking about myself in public? If so, why this… Or was it the nature and relevance of the information that was now being called into question?

The conversation with V. progressed through a discussion of various psychological motivations for social updates – most prominent of which being pure, unadulterated ego. There is no doubt that ego plays a very great part in our participation in social networks. We like people to think we are doing well and take full advantage of the fact that we can doctor the public image we present to people through media such as Facebook. We post images of things we like, because we want other people to think our taste is cool; we untag unflattering photographs of ourselves and post attractive ones because we want people to see us at our best. We tell everyone about what a wonderful lunch we had, what a cool restaurant we’re in, what a wonderful sunset we saw, and post a photo of it so people will think we are living an enviable life and either admire us or be jealous of us. We are proud of our likes and dislikes and wear them like badges on social pages. We assert our opinions because we think they are valid and that others ought to take note. Parents post photos of their children, even going so far as to change their profile shot to one of their child – something I personally find rather disturbing, after all, I’m not friends with the child and I’m not sure it’s appropriate – because they are proud and want everyone to tell them how cute their children are. Through all of this, I doubt very much that the desire is purely one of sharing beauty with other people in the hope of brightening up their lives, but rather it is largely about drawing attention to ourselves as the providers of beauty, wit, opinion and cool things generally.

Of course there are different levels of connection within all social networks and different means of communicating. The “wall” on Facebook is where the public discussion takes place, often very frankly about private issues, but mostly about trivial likes and dislikes or pleasant, but otherwise quotidian experiences, such as eating a good lunch or seeing a good movie. Behind the wall one can initiate a far more intimate conversation about things one genuinely wishes to keep private, and people usually reserve the message format for such purposes. No doubt most of us have had the experience of a public exchange on the Facebook wall leading to a private exchange to determine whether everything is okay after having inferred something from a comment. Equally Twitter allows one to conduct private exchanges with followers, yet the limitations of the 144 character format make it more difficult to conduct a profound discussion.

Not all our expressions on social networks are positive by any means. People very often use Facebook and Twitter to vent, whinge, or lament their circumstances; often in a good-humoured fashion, but also in an angry or unpleasant manner. I certainly have been guilty of this on occasions when the world has seriously pissed me off, or when I’ve felt especially low on account of some personal upset. Such venting will often result in sympathetic responses, but also in ominous silence.

Interestingly, research has shown that because most people post about positive, happy experiences on Facebook, people who regularly use social networking sites often have a more positive outlook on life because they believe that all the important people in their lives are happy and doing well. Equally, however, people prone to status anxiety or those who feel less successful can also experience strong feelings of inadequacy on account of the perception that everyone else is doing better than they are in life. Have you never had that feeling of “Fuck you for having a good time, I’m having a shit one, thanks for rubbing my face in it”? We don’t tend to post such things, but I strongly suspect many of us feel it more often than we are willing to admit.

Generally, however, as is the case with social relationships in all bonded groups in the animal kingdom, particularly amongst primates, the benefits of maintaining social networks far outweighs the negatives. It is why intelligent animals, including ourselves, invest so much energy and make significant sacrifices to maintain social networks. Sustaining a friendship requires a lot of effort – be it baboons grooming each other for extended periods of time, or attending a function we’d otherwise rather not go to.

Our efforts online mirror our real-world social efforts: by liking someone’s post, writing a complimentary comment, or simply “laughing” at a joke, we sustain the sense of unity, trust and like-mindedness just as we would by attending an after-works drinking session or turning up for a BBQ. In reality, most people are capable of maintaining a maximum network of about 150 friends – the so-called Dunbar’s number. This can be broken down to roughly 5 intimates, 15 best friends, 50 good friends, and 150 friends, with, of course, some considerable degree of flexibility according to social skills, gender and personality. It is very difficult for people to maintain more friendships than this, because the effort required is simply too great, and the net benefits diminish as the number grows too large to be economical and sustainable. We may have many more “acquaintances” such as local shop-keepers and colleagues or clients, and there may be an even greater number of people we “recognise”, but Dunbar’s number holds largely true as a relative maximum for most people. Research also indicates that roughly sixty percent of our social time is devoted to our five closest friends, which means the rest is very thinly spread indeed.

So, having said all of this, and having had so many positive experiences on Facebook in particular, why was I now feeling a sense of pointlessness, or even, embarrassment, at the idea of making a harmless, friendly, possibly amusing and entertaining social update? What, I wondered, was my relationship to these connective tools, to these interfaces? Had I shifted away from the spirit of sharing, entertaining and egotistical self-promotion to seeing Facebook as merely an interactive address book? How did I want to use Facebook and for what purpose? Did it matter?

In recent years, I’ve become something of a slacker at reading other people’s updates. I often don’t look at Facebook for days and then get a slightly guilty feeling that I’ve missed something important. And I have missed some seriously big somethings at various points – births, marriages and a whole bunch of special occasions. I long since switched off all the e-mail notifications and I often don’t check the Facebook notifications, so I miss a lot of event invitations in particular. Sometimes I don’t even notice that people have messaged me directly. Then, one day, with the aforementioned feeling of guilt, I’ll plunge into the Facebook log and like a whole lot of stuff, post a comment or two, before clearing off again without waiting to see if anyone replies. It never feels very sincere. It’s not that I’m not interested in what my friends are doing – I am in fact very interested, but I can’t pretend I’m interested in everything they’re doing, just as I hardly expect them to be interested in everything I’m doing. I’m just glad to see my friends happy and prosperous.

What surprises me when I do log in is just how many of my friends seem continually to inhabit Facebook. Some of them appear to be there all day everyday, liking, bantering, commenting, posting… Indeed, more often than not, Facebook resembles a crèche or parents’ club – indicative of my age cohort and demographic – which leaves me feeling conspicuously out of place for not having children. I wonder if this perception has contributed to my gradual retreat from Facebook. I certainly don’t harbour any feelings of negativity or resentment, I just feel a little out of place, and perhaps a tad unnecessary.

So why make a status update? Why tweet? Why tell people what I’m having for lunch and show a picture of it? As I’ve said, I’ve always been a diarist, an historian and a collector, and Facebook makes a great log of one’s life which is immensely satisfying as a repository of experience and communications. I’ve also long been writing creative fiction and non-fiction and taking photographs and I suppose there is an intrinsic inclination in nearly all artists to want to share their work – partly for the sake of recognition, but also certainly because it is pleasing when other people take pleasure in it – for their sake. It is nice to have touched their lives in a positive way and apart from feeling chuffed about my work, compliments always give me a feeling of having done something good and worthwhile.

I suppose it’s a combination of these two principal drives that encourages me to produce material for publication, yet I wonder if I have come to draw some sort of line between art and life. What is the difference between an arty photograph and a photograph of someone’s exotic-looking lunch? Is there a difference when posted on Facebook or anywhere else for that matter?

A part of me thinks that there is a difference, so far as what makes me feel comfortable. In recent times I have become less comfortable with providing purely personal information – where I’m at, what I’m doing, though I have no such qualms about publishing a collection of photographs with some kind of written narrative, or, indeed, posting a piece such as this. I’d like to think that the “art” or discussion is in some way educational, stimulating, provocative etc, just as this piece of writing might be in some way informative and educational. I don’t mean to suggest the photos I take or what I write is some worthy, lofty thing, or that I am in any way superior to other people, it’s really about where I feel I ought to be putting my energies and what I consider a worthwhile form of expression. I guess I have lost the desire to be so open on a day to day basis: where I’m drinking, what I’m having for dinner, what I’m listening to, watching or anything else for that matter, just doesn’t seem relevant to other people.

So, I’m left wondering, have I become boringly anti-social, have I drawn some unnecessary distinction between art and everyday life? I’m not sure, though I do feel less inclined to post purely social updates as I can’t shake the feeling that the only true motivation is to solicit attention, which seems somehow unworthy and makes me feel like a desperate fool shouting “look at me!”

So, sitting there at the bar in Melbourne, I was perfectly placed to check in on Foursquare, Instagram the bar, tweet about the cider and write a status update telling everybody just how bloody great a time I was having, except that, in reality, I was having far too nice a time and a good conversation to want to do any of that. My amazingly capable phone sat idly by, ready to help where necessary, but otherwise content to perform its basic functions of telling me the time and receiving calls and messages.

I suspect this stepping away from social networking is a phase. When I was single I continually inhabited the net, because I really wanted to make connections. I turned the Facebook instant messaging service back on, I put profiles on several dating websites and played the game hard, constantly instigating and answering e-mail conversations with prospective partners or bed buddies. Now, in retreat from unnecessary contact and communication – which is time-consuming and often undesirable – I feel somewhat reassured that my motive was not purely egotism, but the desire to find a cure for loneliness. Should I ever find myself single again, which I sincerely hope will not be the case, then I imagine I’d take up Facebook and Twitter again, along with other connective interfaces, with enthusiasm. For now, however, I need to find the motivation to do the bare minimum to sustain my existing friendships – which is challenging enough in itself!

ps. As a final irony, I’m now going to post this on Facebook and Twitter : )

Posted in Memoir, The Odyssey of Life | 2 Comments »

The two greatest heroes of my adult life are not people, but machines: the twin Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity. This apparent idolatry might seem almost fundamentally misanthropic or oddly fetishist, yet rather it is born of a tendency to personify and anthropomorphise everything. David Attenborough remains firmly in place as my favourite human, alongside several mentors and acquaintances from whom I’ve had the good fortune to draw inspiration and wisdom. Yet no one, nor anything for that matter, in recent memory, has achieved the level of admiration I have developed for the two Mars rovers.

The rovers were of identical design and carried a range of instruments with which to carry out geological exploration: Panoramic cameras, a Thermal Emission Spectrometer for identifying and closely examining rock types and profiling the temperature of the Martian atmosphere, a so-calledMössbauer Spectrometer for closer investigation of rock mineralogy, an Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer for analysis of the elements that make up rocks and soils, magnets for collecting dust particles, a microscopic imager for high-resolution imaging of rocks and soils, and a Rock Abrasion Tool for exposing fresh material beneath the rock and dust. Despite their six-wheeled design, the rovers were, in effect, made to mimic a human geologist, with the panoramic camera mounted on a 1.5 metre-high mast and a robotic arm which replicated the movement of a human elbow and wrist. The microscopic camera and rock abrasion tool in the rovers’ “fist” were designed to replicate the work of the geologist’s magnifying glass and hammer. With these sophisticated tools, it was hoped that the two rovers would be able to provide sufficient evidence to support the wet-Mars theory.

The two missions were launched on June 10 and July 7, 2003 and successfully landed on Mars on January 3 and January 24, 2004. The principal goal of both missions was to search for evidence of water, or a history thereof, and the rovers were sent to two different locations on opposite sides of Mars: Spirit to the Gusev Crater – a possible ancient lake-bed, roughly 14 degrees south of the Martian equator, into which the Ma’adim Vallis channel system drains, and Opportunity to the Meridiani Planum – a plain just two degrees south of the equator in the westernmost portion of Terra Meridiani, which hosts a rare occurrence of gray crystalline hematite. Hematite is usually found in hot springs or pools of water on Earth, whilst the apparent channels at Gusev closely resemble natural water courses on Earth. Hence both sites held promise of answering the question as to whether or not the surface of Mars was once partly covered with liquid water, which was strongly believed to be the case.

It is a difficult enough job landing a probe successfully on Mars – as several expensive failures have proven – let alone communicating with and driving a rover on the surface. The first successful landings on Mars were the two Viking missions of 1975, which arrived in 1976.

Both missions consisted of orbiting probes and landers, which were highly successful in providing detailed images and information about the surface of Mars, paving the way for future missions. Both landers were not mobile; they were designed to act, in effect, as stationary laboratories, testing soil samples for evidence of microbial life or organic compounds. The Viking 1 and 2 landers operated for six years and three months, and three years and seven months respectively, an extraordinary achievement in itself.

Despite this lengthy operation time, neither lander was able to discover any biosignatures that might suggest life was present or had previously existed on Mars.

Ultimately the missions only ended when the landers and orbiters failed in various ways, one by one. Whilst Viking 2’s battery failed in 1980, the tragic death of Viking 2 on November 13, 1982, was due to human error – during a software upgrade the antenna was accidentally retracted, permanently shutting off communication and terminating the mission.

It was not until 1997 that another probe successfully landed on the surface of Mars: the Pathfinder mission, which also consisted of an orbiter and lander. The major difference with the Pathfinder mission was the introduction of a mobile, roving lander -Mars Sojourner. Sojourner was just a little guy – a mere 65cm by 48cm, with a height of 30cm – it weighed in at just over ten kilograms. Operating in the Ares Vallis “flood plain”, one of the rockiest places on Mars, roughly nineteen degrees north of the equator, Sojourner’s rock analysis was able to confirm a history of volcanic activity on Mars, along with identifying erosion patterns consistent with wind and water erosion.

The mission was designed in large part as a proof of concept – that rover missions could be sent to Mars successfully for a fraction of the cost of the vastly expensive Viking missions, and to test new technologies, particularly the means by which craft were landed on other planets. Pathfinder used an innovative airbag system and effectively bounced along the surface like a giant ball.

The Pathfinder mission was considered a resounding success on all fronts – in cost-effectiveness, research significance and mission duration, which was extended two months beyond its initial target of just one month. During a mission of 83 sols (1 sol = 1 Martian day, approximately 24 hours, 39 minutes) Sojourner travelled a total of roughly 100 metres, never venturing more than 12 metres from its base-station. We thus have many lovely images of Sojourner at work on Mars photographed from its base station, a rare treat for a rover mission.

Without Pathfinder’s pioneering efforts, the successful landing of Nasa’s Spirit and Opportunity probes might not have been so easily achieved. Not to suggest for a second that it is ever easy to land a probe on another planet.

There is much more that could be said about human exploration of Mars by proxy – the Mars Voyager missions, the failed Soviet attempts to land a rover in the 1970s, the Mars Global Surveyor, the more recent Phoenix mission which landed in the northern polar region and after a successful operation, froze to death during the bitter winter, but that would be to stray too far from the base-station, as it were, and require far too many words.

Returning to the topic at hand, I’d first like to mention the dedicated teams of men and women behind Nasa’s Mars Exploration Rover Missions. From the mission designers to the people who control and monitor the activity of the rovers, to the scientists who examine the data returned by the probes, many thousands of hours of hard graft have gone into this project. Not only have the teams at Nasa worked long and gruelling hours, those controlling and monitoring the rovers have been forced to operate on Martian time – a 24 hour, 39 minute and 35 second day, sometimes for months on end. Team members were issued with special watches and expected to adjust their schedule to stay in alignment with Martian time – meaning roughly forty minutes of jet-lag every day! The watches were also fitted with accelerometers as part of a study into the effects of such a time-cycle on the human body and mind. This is no mean feat, especially when we consider that initially the mission was due to run for three months in total and yet, it is still going – eight years (!) after the rovers first landed on Mars.

It is for this reason that I have become so deeply attached to these brave little rovers, and, it must be said, to those who have kept them running through all this time. Just recently, in June 2012, Opportunity, after waking from a semi-sleep during the Martian winter, provided us with a stunning panorama of the location at which it stopped to rest back in January.

Opportunity is not only still alive, but it is doing very well in a cold world of rock, sand and fine dust. With temperatures ranging from between -5 to -87 degrees Celsius, Opportunity has survived not only freezing conditions, but also dust storms and getting bogged in a sand dune.

During the last eight years, Opportunity, which was designed to travel up to forty metres a day for a total odometry of roughly 1 kilometre, has travelled a distance of just over thirty-five kilometres. Opportunity landed, by chance, in an impact crater dubbed “Eagle” in an otherwise flat plain. On account of its airbag-aided bouncy landing, the mission controllers could hardly predict exactly where either probe would land, and the landing in Eagle was referred to humourously as a hole-in-one. It also proved to be of immense scientific interest, particularly a sedimentary outcropping dubbed El Capitan. Despite being unable to determine whether or not the layers of sediment were deposited by volcanic ash, wind or water, the discovery of the mineral Jarosite, containing an abundance of hydroxide ions, indicated it had formed in water. When Opportunity dug a trench and exposed more of the rock, it uncovered small hematite spheres, nicknamed blueberries, which are strongly believed to have formed in water. Already the mission was proving a resounding success.

Leaving the Eagle Crater, Opportunity travelled to another crater, Endurance, which it investigated between June and December 2004, methodically working its way into and around the crater.

When it moved on, Opportunity passed the some of the debris from its own heatshield, and, in an unexpectedly fortunate discovery, an intact meteorite, now known as Heat Shield Rock, was discovered nearby. This proved to be the first meteorite identified on another planet.

Shortly afterwards, as it drove towards the so-called Erebus Crater, Opportunity became perilously stuck in the sand – a problem that took six weeks to solve via Earth-based simulations, which were then successfully implemented.

Erebus Crater was a large shallow, partially buried crater, with a significant number of rocky outcrops to explore. Of course, the mission of the rovers was not merely to study the geology of the planet, but whilst at Erebus, Opportunity also photographed a transit of Mars’ moon Phobos across the face of the sun.

In September 2006, Opportunity arrived at the even more spectacular Victoria Crater. It explored the rim of the crater in detail, before returning to its original arrival point, Duck Bay. The wonderful panoramic views of the crater are some of the most evocative ever to come from the surface of another planet.

The rippled sand at the centre of the crater also makes a very alluring photographic subject.

In June of that year, Opportunity entered the crater where it remained until August 2008, conducting various analyses of the rocks and soil.

Without wishing to go into too much further detail about Opportunity’s journey across the surface of Mars, it will suffice to say that over the following years Opportunity made several stops at various other craters, including Conception, Intrepid and Santa Maria.

Ultimately, Opportunity’s destination was the much larger Endeavour Crater – no less than 23 kilometres wide – which it reached in August 2011. After spending another freezing winter sitting on the crater’s rim, Opportunity is now back in operation, doing what it does best – sophisticated geological investigation.

Of course, Opportunity has not merely been cruising about the surface taking photographs of the Martian landscape. During its travels the roverhas made many important observations and discoveries which have greatly expanded our understanding of the red planet. Principal among these were the identification of spherules – concretions which form in water, vugs – voids in rocks left by water erosion, and sulfates, which on Earth generally form when standing water evaporates. Whilst the data has been rigorously subjected to all alternative hypotheses, the nature and context of the evidence convincingly suggests the prior presence of liquid water on the surface of Mars. So much so, that this is no longer in dispute. We cannot as yet prove that there was once life on Mars, or that it may indeed continue to exist there in some form, yet we can now confidently say that Mars was once wet, and consequently, would have provided almost ideal conditions for life to emerge.

Opportunity has so far performed well beyond all expectations and provided vast amounts of data about the nature of Mars. The sheer length of the mission, and the incredible utility of having a working, mobile rover on the surface of Mars, means that more discoveries are inevitable. The Nasa website for the missions contains archives of the raw photographic images taken by both Opportunity and Spirit, along with logs of the rovers’ progress for each day of the mission, should anyone wish for more detail about the progress of the rovers. Sadly, however, whilst Opportunity continues to provide valuable data and sustain a proxy human presence on Mars, the same cannot be said of its twin, Spirit.

The Spirit rover had a rather more difficult life on Mars from the very beginning. On January 21, a mere eighteen days after its arrival, Spirit suffered a crippling problem with its flash memory that threatened to end the rover’s mission prematurely. The rover seemed to be stuck in an endless reboot loop and was not responding as it should. It was not until the 3rd of February that mission controllers identified the problem as a file-system error and remotely reformatted the entire flash memory system, allowing Spirit to resume its mission.

To make matters more difficult, the Gusev crater site where Spirit landed, turned out not to be a sedimentary lakebed after all, but rather a plain of volcanic material. Spirit was sent as fast as possible across the plains to the so-called Columbia Hills, which were believed to be geologically more ancient.

Spirit made numerous pitstops en route, perhaps most notably at the so-called Humphrey Rock, a volcanic rock which appeared to show evidence of liquid water flow in its formation.

Little of interest was found at various other craters which Spirit passed, and eventually, after 129 Sols, Spirit finally clambered up the slopes of the Columbia Hills. Over the following two years, Spirit explored these hills– places with names such as Husband Hill, Cumberland Ridge, Larry’s Lookout, Tennessee Valley, Home Plate, McCool Hill, Low Ridge Haven and so on.

In 2006, Spirit finally came down from the hills to explore an area known as Home Plate, where it was to remain for the rest of its working life. Home Plate turned out to be a large “explosive” volanic deposit, surrounded by basalt which is believed to have exploded upon contact with water. The presence of salty water seemed confirmed by the high concentration of chloride ions in the surrounding rocks.

Throughout this time, Spirit encountered more difficult conditions and mechanical problems than Opportunity. One of Spirit’s front wheels had long been playing up, and on March 16, 2006, the wheel stopped working altogether. Spirit attempted to crawl backwards, dragging its wheel, to the north face of McCool Hill, where it was to spend the Martian winter, yet was unable to manage the ascent and was instead sent to winter in Low Ridge Haven.

The broken wheel on Spirit laterturned out to be a blessing of sorts, when its dragging through the soil uncovered a subsurface layer of silica rich dust in December 2007.

The resulting analysis suggested the silica was likely produced in a hot-spring environment, again suggestive of a water-rich history.

The site near the Gusev Crater was especially dusty and throughout its mission, Spirit’s solar arrays faced increasingly reduced capacity on account of the dust coating.

In 2007 dust storms threatened to shut Spirit down altogether, reducing the production capacity of its solar panels from 700 watt-hours per day to a mere 128, below the minimum threshold for sustaining battery charge to power the rover’s heaters.

To avoid risk of the rover shutting down completely, Spirit was kept in temporary hibernation on its lowest possible power setting. For two weeks between November 29 and December 13, 2008, on account of the so-called Solar Conjunction – when the sun is between Earth and Mars –no communication was possible with either rover.

Even when Spirit revived from its troubled hibernation, its solar arrays still struggled to produce sufficient power. It was not until February 2009, when a fortunate wind cleaned some of the dust off Spirit’s panels, increasing its energy production to roughly 240 watts per day, that the rover seemed ready to reach full exploration capacity once again. Unfortunately, however, on the first of May 2009, Spirit became stuck in soft soil and proved unable to free itself. With the failure of another wheel, the engineers and controllers were unable to extract Spirit from its location after numerous attempts to do so, via various simulations and manoeuvres. Eventually the rover’s purpose had to be redefined as a stationary research platform, but in truth, Spirit’s run had come to an end. The last communication was on March 22, 2010, the 2210th day of the mission. The cold, it appears, was the ultimate culprit. In previous winters, Spirit had been able to park itself on a sun-facing slope, allowing it to winter in temperatures averaging -40. Stuck out on the plains, however, Spirit endured temperatures of closer to -55 Celsius – more than its reduced energy production could cope with.

Many attempts were made to regain contact with Spirit, and it was not until May 2011 that the mission was officially declared over. The final entry for Spirit’s log on the Nasa website reads as follows:

SPIRIT UPDATE: Spirit Remains Silent at Troy – sols 2621-2627, May 18-24, 2011:

More than 1,300 commands were radiated to Spirit as part of the recovery effort in an attempt to elicit a response from the rover. No communication has been received from Spirit since Sol 2210 (March 22, 2010). The project concluded the Spirit recovery efforts on May 25, 2011. The remaining, pre-sequenced ultra-high frequency (UHF) relay passes scheduled for Spirit on board the Odyssey orbiter will complete on June 8, 2011. Total odometry is unchanged at 7,730.50 meters (4.80 miles).

Despite its incredible successes and the unimaginable extension of its mission, the loss of Spirit was a great disappointment for the mission controllers. Once it had become clear how well the rovers were performing on Mars, Nasa had made the decision to drive them until they broke down, and this was certainly the fate of Spirit. When the mission was finally abandoned, Mars Exploration Rover Project Manager John Callas, sent a letter to his team, both celebrating and farewelling the great success of the tough little rover. An abridged version follows:

Dear Team,

Last night, just after midnight, the last recovery command was sent to Spirit. It would be an understatement to say that this was a significant moment. Since the last communication from Spirit on March 22, 2010 (Sol 2210), as she entered her fourth Martian winter, nothing has been heard from her. There is a continued silence from the Gusev site on Mars.

Importantly, it is not how long the rover lasted, but how much exploration and discovery Spirit has done.

Each winter was hard for Spirit. But with ever-accumulating dust and the failed wheel that limited the maximum achievable slope, Spirit had no options for surviving the looming fourth winter. So we made a hard push toward some high-value science to the south. But the first path there, up onto Home Plate, was not passable. So we went for Plan B, around to the northeast of Home Plate. That too was not passable and the clock was ticking. We were left with our last choice, the longest and most risky, to head around Home Plate to the west.

It was along this path that Spirit, with her degraded 5-wheel driving, broke through an unseen hazard and became embedded in unconsolidated fine material that trapped the rover. Even this unfortunate event turned into another exciting scientific discovery. We conducted a very ambitious extrication effort, but the extrication on Mars ran out of time with the fourth winter and was further complicated by another wheel failure.

With no favorable tilt and more dust on the arrays, Spirit likely ran out of energy and succumbed to the cold temperatures during the fourth winter. There was a plausible expectation that the rover might survive the cold and wake up in the spring, but a lack of response from the rover after more than 1,200 recovery commands were sent to rouse her indicates that Spirit will sleep forever.